The Texture of Innovation

“Do you know why books such as this are so important? Because they have quality. And what does the word quality mean? To me it means texture. This book has pores. It has features. This book can go under the microscope. You’d find life under the glass, streaming past in infinite profusion. The more pores, the more truthfully recorded details of life per square inch you can get on a sheet of paper, the more `literary’ you are. That’s my definition, anyway. Telling detail. Fresh detail. The good writers touch life often.” Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451 (Emphasis added)

Let me suggest innovators gain tremendous power considering their work for whether it delivers what Bradbury describes as “texture”.

Wait, what? Wouldn’t that be fuzzy & non-technical? This absolutely is a non-technical way to consider work. And it is without question an evaluation which must not be reduced to metrics (see Deming below). Still, considering texture can offer tremendous insight.

After all, when we put innovative products we love under the microscope we find interesting things:

- They hold up as we examine them further & further.

- They feel more valuable, not less, the more we use them.

- There is usually more to discover in the product than what we use today (and already find quite valuable).

- We know the product strengths so that we use the product without it letting us down.

- The innovation is core to the thing we value in the product.

- We hear the same things from others who own them.

So how do we create products that have this texture?

There is no simple answer to that question. But let me suggest that most critically needed is that innovation permeate your process.

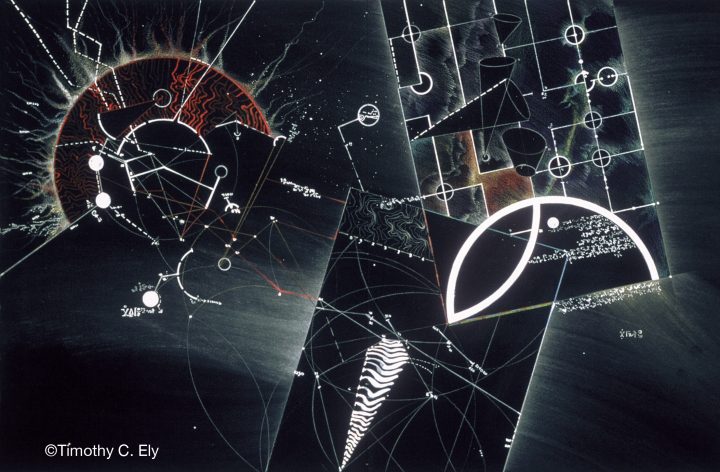

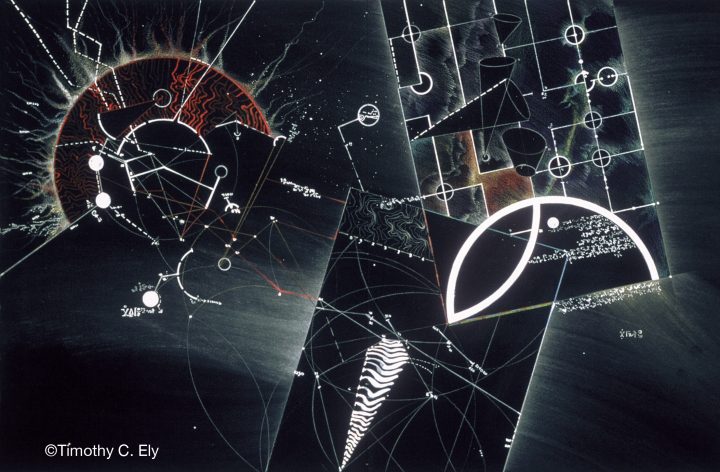

I was talking with artist Timothy Ely, a good friend, over the weekend (one of his works is shown above). Tim observed how frustrating it is when people think the primary step to great art is the “idea behind it”. In truth, he observed, a work only becomes great because (a) it starts with a good creative idea and (b) tremendous creativity is applied all the way through making the final artifact (painting, drawing, sculpture, book, movie, etc…) exude the energy that he feels defines art.

Only continued and constant creativity while making can end up delivering a great work of art. This is an apt description of innovation processes. The “idea” of the innovation is merely the beginning. What matters just as much is a continual application of innovative solutions throughout the creation, and marketing, of the product.

Innovation teams must always be looking and watching – especially remaining open to the instinctive or irrational. If someone has even the tiniest instinct of hesitation – they must examine it. That instinct will likely point to a change that leads to a product with far better texture. And when they see something that won’t hold up under scrutiny, it must be dealt with – even late in the project. Only a disciplined process which pays attention to instincts produces a brilliant result.

This isn’t likely to make senior management or the board comfortable. But corporations with a solid future learn to put up with the discomfort required for fundamental innovation. Engineering and marketing management must not give into demands from upper management that they use a “reliable, repeatable process” which turns innovation into a checklist.

As I wrote last week, innovation is not a tame practice.

This post may, I suppose, make some from b-school or engineering uncomfortable. This IS a fuzzy description and many engineers and product managers hate fuzziness. I understand that response. Yet 35 years in innovation have taught me that the most critical truths are often found where things feel fuzzy.

And we must not create a metric for texture. While many believe W. Edwards Deming to be a dour statistician who demanded measurements for everything, quite significantly he wrote:

“…the most important figures that one needs for management are unknown or unknowable (Lloyd S. Nelson, director of statistical methods for the Nashua corporation), but successful management must nevertheless take account of them.” W. Edwards Deming, Out of the Crisis

So let me suggest embracing this idea of texture. And let’s use it to consider the many Deming “unknowables” which surround innovation. Do that well, and you’ll find more dramatic success.

Copyright 2018 – Doug Garnett – All Rights Reserved

Artwork “Black Maps” used with permission of copyright owner Timothy C. Ely.

Categories: Innovation