Surviving Disruption. Kodak Storytellers Get It Wrong; Things We Can Learn from Kodak, Fuji, Supercomputers and NordicTrack.

There are case studies. And there are morality plays told by consultants to sell us their services. Nowhere, today, are there more morality plays than with mythologies around “disruption”.

One particular disruption story stands out — the one written around Kodak. It’s quite popular and repeated regularly as an absolute truth.

About Business and Fairy Tales

It turns out the Kodak disruption story is wrong. And, yet, as a race we humans are quite resistant to learning truth after living with a fairy tale. As Josephine Tey wrote in The Daughters of Time:

It’s an odd thing but when you tell someone the true facts of a mythical tale they are indignant not with the teller but with you. They don’t want to have their ideas upset. It rouses some vague uneasiness in them, I think, and they resent it. So they reject it and refuse to think about it. If they were merely indifferent it would be natural and understandable. But it is much stronger than that, much more positive. They are annoyed (36, p. 119).

So let’s search for the true facts of Kodak’s demise (a search which continues in another blog post looking at Kodak’s demise and Fuji’s success).

The Kodak Disruption Fairy Tale

The Kodak Tale, like any great morality play, has a simplicity which neatly fits all of our expectations and fears around business failure. In it’s basic form (often embellished but never changed), the Kodak story goes like this:

- Kodak was an archaic business because they sold photographic film.

- Digital replaced film, so Kodak needed to shift to digital.

- Kodak screwed this up. They HAD great digital cameras and blew it.

- So Kodak is out of business because they failed to shift to digital.

Listeners mostly nod their head in agreement because the story fits the key disruption narrative where executives are too tied to the past to change. It also fits a whole range of popular “digital transformation” narratives — the “digital divide”, “going digital”, “the digital helix”, “digital DNA” — which have become religious dogma accepted by the digerati.

But here’s the thing: When any story fits the narratives perfectly we should take that as a red flag — we should be skeptical.

Kodak’s Story is Much More Complicated

Here are some deeper truths.

- Kodak was a film company — not a camera company. “Going digital” didn’t replace film — it replaced cameras and film at the same time. To conquer the digital business Kodak would have had to become a camera company. It wasn’t a question of “just go digital” but of changing from a film and processing company to a digital camera company. This was a tough road but it could have been done. But would there be sufficient profit for all the hard work?

- Kodak’s strength was built on the high margins of the film business. Film is not easy — a complicated chemical process, lots of subtlety, retail distribution of film as well as film to be developed, etc… They created a superb film company which generated high margins — their entire business structure was built around making that work brilliantly. Usually we’d call that building a good business.

- Kodak embraced digital early. Kodak did not ignore digital advances. We are told Kodak had some of the best digital technology from a very early date and their early digital cameras were phenomenal. So what did they learn through that experience? Digital cameras are a dog-eat-dog competitive world of low margins — and a world already dominated by exceptionally strong CAMERA brands. In other words, they would have learned that running after digital was a dead end because of low profits.

- Even if Kodak had figured out how to become a digital camera company, it wouldn’t have mattered. Within a decade of the explosion of digital cameras, smart phones exploded and took huge amounts of business from digital cameras — essentially offering the same capabilities for free. Camera manufacturers have struggled since and so would Kodak even if they’d been able to license technology onto each smartphone.

- Kodak’s survival depended on whether there were any viable paths outside of the photography market. I don’t know if there were because I don’t know what opportunities presented themselves nor which potentials could would have led to long term financial strength. But I do know the morality play around Kodak is wrong.

A First Lesson: Stop Listening to Monday Morning Quarterbacks

This Mashable article is a classic example of Monday Morning Quarterbacking Kodak. I’m particularly struck by Jeff Hayzlett’s comments. As the last Kodak CMO with an opportunity to turn it around, I’d expect him to be more careful in assigning blame. Especially these claims that Kodak “missed” 3 key digital opportunities. Note the incredible lack of profitability among these “missed” opportunities. We need to be honest that Kodak wouldn’t have saved itself by establishing a money-losing photo sharing operation.

JP Hanson, CEO at Rouser, has observed about stories like this:

…the decision is analyzed based on a dependent variable (the outcome). The problem, however, is that we can’t see into the future {from today}, so the only thing we should analyze is whether the decision made strategic sense at the time, given what they knew then.

Fortunately, we can look at a related situation that turned out much differently.

Fuji Also Depended on High Margin Film & Survived. How?

An interesting analysis has been written comparing Kodak’s path and Fuji’s path. This article deserves serious consideration. Some things I take away after reading this article and pondering Kodak:

- It’s nearly impossible for a high margin company to shift to become a low margin company.Many have tried – most (all?) have failed. Business structures do not change that rapidly.

- Fuji decided NOT to chase the photography market down a dark digital, low margin hole. Instead, they followed their strengths where they led and remained a film company – retaining their decades of sophisticated experience.

- It’s not wise to discard your strength. If Kodak had chased digital photography, they would have given up the asset they’d built in their learning — the asset which had built them into what they were. That’s NOT smart business. Rather, throwing out hard earned learning is a route to failure.

- Fuji pivoted and followed their film strengths. Fuji had superb technology with decades of learning which could take it to new places. So they went out to find which places needed their advanced capabilities and they found them.

The article oversimplifies Fuji as a business – perhaps hoping for clarity. I discuss more about Fuji’s truths in another post.about Fuji’s truths in another post.

A Second Lesson: Attempting to Stay in Your Market May Guarantee Failure

Fuji survived by choosing NOT to run after digital — instead doubling down on their strength (film) then taking it to new markets like high end film for etching silicon chips and other high end industrial applications.

My guess is that Kodak’s decisions were nowhere near as irrational as the stories (like the one linked above) want to make them sound. Underneath their apparent commitment to remain a consumer brand they must have fundamentally found that chasing digital was a profitless path to destruction.

I hesitate to blame Kodak’s team — but won’t absolve them of blame either. All we know is where they ended up. Maybe, along the way, they misled themselves with disruption hype and looked all the wrong places. Maybe they chose to believe their consumer brand asset was more valuable than their knowledge asset with film. Maybe, even, they did what all the digerati said they should do and found each to be a dead end. But, also, it could be that they did all the right things yet the same fates which bring together emergent opportunities for incredible success brought them emergent catastrophes no company can survive.

All this bring up an interesting hypothesis: Faced with disruptive forces, attempting to stay in your market might be exactly the path to failure.

Read on. Two examples where I was deeply involved seem to support this hypothesis — who also faced tsunami’s of disruptive change.

Supercomputer Disruption in the Early 1990s

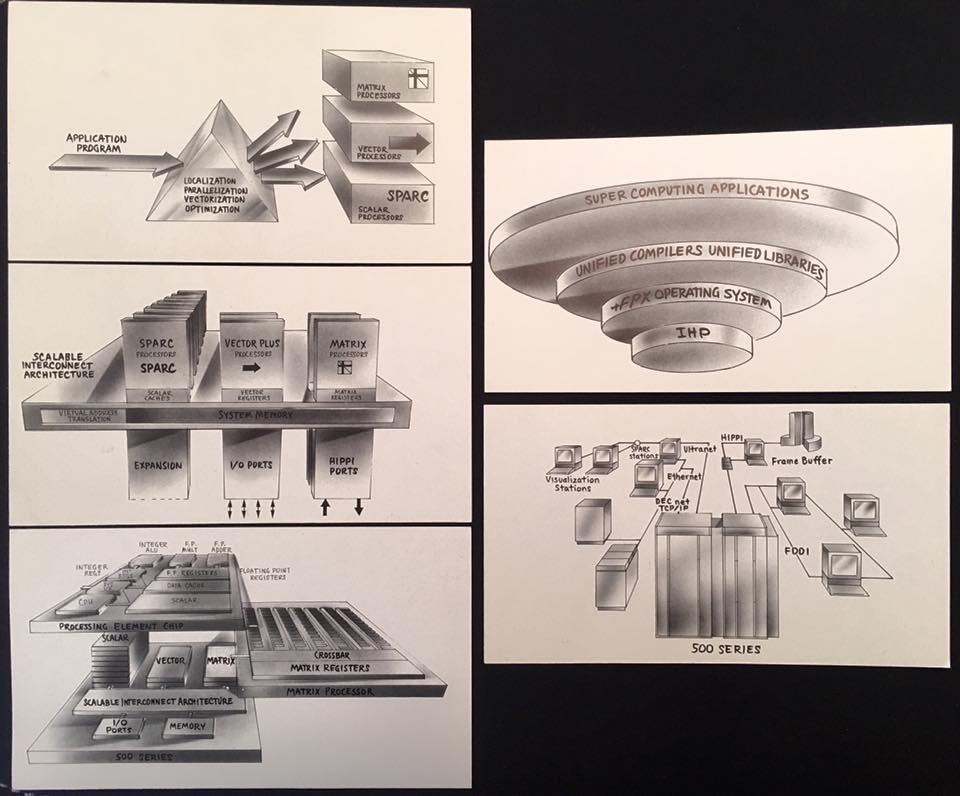

I was fortunate to be a sales engineer, salesman and manager of international marketing for Floating Point Systems from 1987 through 1991. It was a great job and I worked with an incredible set of executives and colleagues.

While FPS had pioneered attached vector processors, by 1991 we made unix based supercomputers. In a key strategic shift we made our architecture SUN/SPARC compatible looking for significant advantage against competition.

Then disruption arrived — in the form of computers based on high speed integrated chip sets. These were offered by Silicon Graphics and others.

Suddenly we had to sell a marginally faster $800,000 computer requiring a computer room with halon fire suppression against a $200,000 computer that sat next to a scientist’s desk and was more reliable than our big iron (due to fewer chips). In a time-span of roughly 2 years, the entire supercomputer business evaporated.

Disruption moralists would claim our team was stupid and caught flat footed. They weren’t.

In my role pitching the computers internationally, I was in close contact with our engineers and know they were right on top of the shift to IC chip sets. In the end, we couldn’t afford to take advantage of them. Huge investment was required yet we were a low unit volume, high margin company. SGI, by contrast, was already a lower margin, higher volume supplier and were able to spread that investment successfully.

The FPS Story Is Fulfilled at Sun Microsystems

FPS couldn’t compete — but neither could Cray or Hambrecht & Quist poster child Convex (who leapt aboard the sinking Compaq ship). In 1991 FPS declared bankruptcy and their assets were bought by Cray, who was bought by SGI who sold the FPS operation to Sun Microsystems because of the SPARC architecture. Folks like my good friend Shahin Khan continued their work at Sun.

Shahin Khan, FPS colleague, HPC expert and, at this time, VP-Strategy at Sun with some big iron.

AND THEN…Sun embraced the FPS team for what they did well — building “big iron” UNIX machines. The former FPS team pivoted these strengths to business computing. And through Sun they obtained sufficient funding to make Sun’s high end servers throughout the 1990s.

They did ok. Like $8 billion of ok from what I’m told. That’s right, they sold $8 billion (with a “B”) worth of big iron during the 1990s. How? Their pivot was in the direction of their strengths instead of chasing the market to the bottom.

A Look at NordicTrack. Different Situation, Same Truth?

Founded in 1975, NordicTrack’s ski machines took the world by storm in the 1980s. But in 1998 this market leader reached it’s end and was bought by their primary competitor. What happened? I had a ringside seat along some of this journey because in the 1990’s I did key strategic work for fitness products — including strategic work for both NordicTrack and their primary competitor Proform.

Founded in 1975, NordicTrack’s ski machines took the world by storm in the 1980s. But in 1998 this market leader reached it’s end and was bought by their primary competitor. What happened? I had a ringside seat along some of this journey because in the 1990’s I did key strategic work for fitness products — including strategic work for both NordicTrack and their primary competitor Proform.

NordicTrack’s vulnerability was different from Kodak’s or the supercomputer business. NordicTrack’s success came by being the ONLY lower cost ($1,000) aerobic fitness machine available for the home. In the 1980s they leveraged this into excellent sales and grew quickly.

What they failed to honor was how frustrated their machine made couch potato customers — it required excellent dexterity to use well. This extended in the 1990’s to a mandate to never show anyone sweating while working out. As a result, NordicTrack was exceptionally vulnerable to an easier to use competitor at the same — or even a slightly higher — price.

Then something worse happened: ProForm Fitness came out with a machine that was easier to use — a treadmill — at half the price. They ate NordicTrack’s lunch.

Could NordicTrack Have Survived by Embracing It’s Strengths? Maybe.

Consumer research showed that NordicTrack’s challenging use was also a tremendous strength — providing an better aerobic workout in the home than any other machine. In research, I heard users talk about endorphin rushes and physical reactions only possible the best of intense workouts.

Consumer research showed that NordicTrack’s challenging use was also a tremendous strength — providing an better aerobic workout in the home than any other machine. In research, I heard users talk about endorphin rushes and physical reactions only possible the best of intense workouts.

So I recommended that NordicTrack embrace their strength and pivot to athletes. In fact, communication around an idea like “are you athletic enough for NordicTrack?” might have been distinctive enough to bring new vitality to their fading brand.

Whether it might have worked we will never know. It appeared to me that management struggled to accept the seriousness of their situation — they wanted to believe their problem wasn’t so severe. Sympathetically, they also faced a disconnect between building their company for a couch potato sized market and this would have likely narrowed their unit sales — at least for a time.

Interestingly, this potentially successful strategic direction follows Fuji and FPS: pursuing what they did well and taking it to new markets or new market focus.

It’s Time to Put Disruption Exaggerations Back in Pandora’s Box

I’ve written about how disruption mythology too often distracts companies from pursuing exactly the innovations that WOULD lead to strength. Part of the problem we fight today is that when Clayton Christensen introduced “disruption”, he opened a Pandora’s box. The idea of disruption hit a nerve then became things he hadn’t ever said.

The young and the frustrated began to loudly proclaim that “everything” needs to be “disrupted” (something we continue to hear). Within tech, the nerve he hit was even more sensitive, in an industry weaned on utopian sci-fi mythology, and many presumed disruption would bring those utopian visions to life…today — thereby ending their frustrations with management and life.

Disruption chaos built further when startup ventures and investors realized that the press and public were suckers for a claim of “disruption” — every new thing began to be claimed to be a “disruptor”.

It’s time to pull back from the abyss. The next time someone puts forth a simplistic disruption morality play, be an immediate skeptic. Only when we’re disciplined against knee jerk reaction can innovators get back to the hard, and truly rewarding, job of building and running successful businesses.

©2019 Doug Garnett — All Rights Reserved

Through my company Protonik, LLC based in Portland Oregon, I work with clients to drive innovation success with better marketing of new and innovative products and services — work which needs to start before market analysis. I also work with clients attempting to bring new life to Shelf Potatoes or take their existing products to new markets. You can read more about these services and my unusual background (math, aerospace, supercomputers, consumer goods & national TV ads) at www.Protonik.net.

Categories: Complexity in Business, Innovation

Posted: March 13, 2019 17:12

David Amerland

Posted: March 18, 2019 09:55

Jacques

Posted: March 18, 2019 14:11

Doug Garnett

Posted: March 18, 2019 19:23

Jacques

Posted: March 18, 2019 19:40

Doug Garnett

Posted: April 30, 2019 20:15

Surviving Disruption, Part 2: Kodak Died. FujiFilm Thrived. Why? | Doug Garnett's Blog