Differentiation & Distinction, Part II: The Emergent Decision to Purchase

Just over a week ago we looked at how the practices of Differentiation and Distinction are fundamentally different with respect to time. We saw, in this analysis, that differences in a product may matter to a consumer for only a very short time then leave behind a conclusion to prefer a product. By contrast, distinctiveness matters for a brand and must be stable and continual through time in order to be effective.

Continuing to explore the complex nature of these qualities, in today’s post we look at the role of each in complex emergence.

Differentiation & Distinction are NOT Ultimate Goals

What we are discussing is typical in marketing — two items which have been abstracted or isolated from among all the many things marketers can focus on. They are defined, then, as key ways companies can influence their ultimate results. What ultimate results? This is a discussion about customers buying a company’s products — both in the short-term and the long-term. Neither of these ideas matter except for how they help cause that ultmate result.

Once we understand complexity, we can clearly see that any purchase is an emergent result. Wait, a choice to buy emerges? Of course it does. Customers are awash with factors which might influence their purchases. Their decision to purchase “emerges” as a result of a massive range of interactions among those factors. Thus, a decision to purchase is not only logical, not only emotional, and not only a balance of these two. Any purchase is influenced by many factors — cultural, instinctive, logical, emotional, rational, product related, information, lifestyle, needs, problems, desires, and much more — which wash around the consumer.

Difference and distinction are two of these factors. They have been separated out because focus on these ideas can help companies cause more purchases to emerge from more consumers. As a result, neither distinction nor differentiation are results we seek. They are possible “levers” experience indicates can help increase sales, revenues on those sales, and profits on the whole shebang.

Laying Out an Emergent Situation

In an emergent situation an ultimate result cannot be predicted by studying the parts in isolation. We only come to a sense of causality in these situations by observing what emerges and learning about how different parts influenced — or were causes — of the result. After all, when parts are interconnected such that they interact with each other and the environment around them — and also adapt through those interactions — the result of those interactions is something different from a sum of the parts.

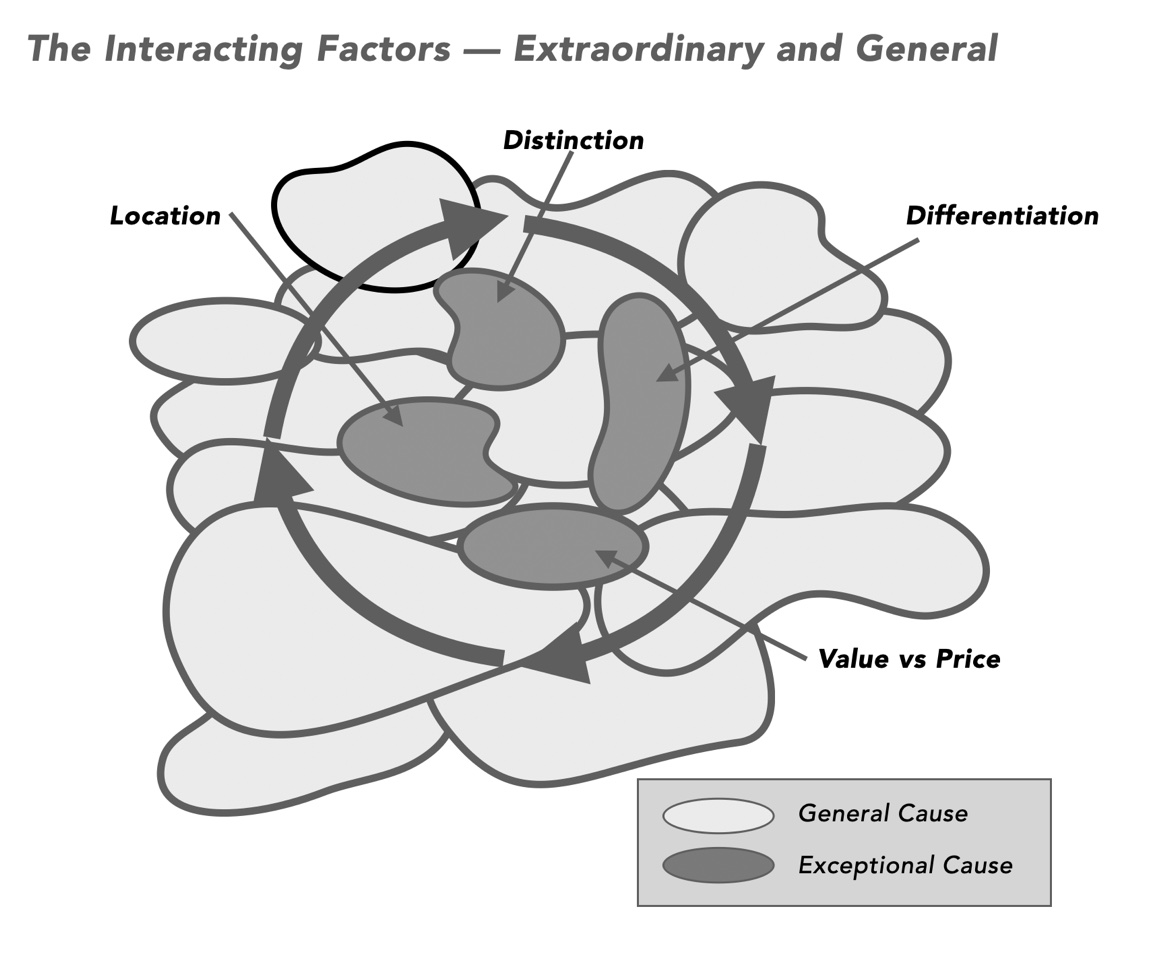

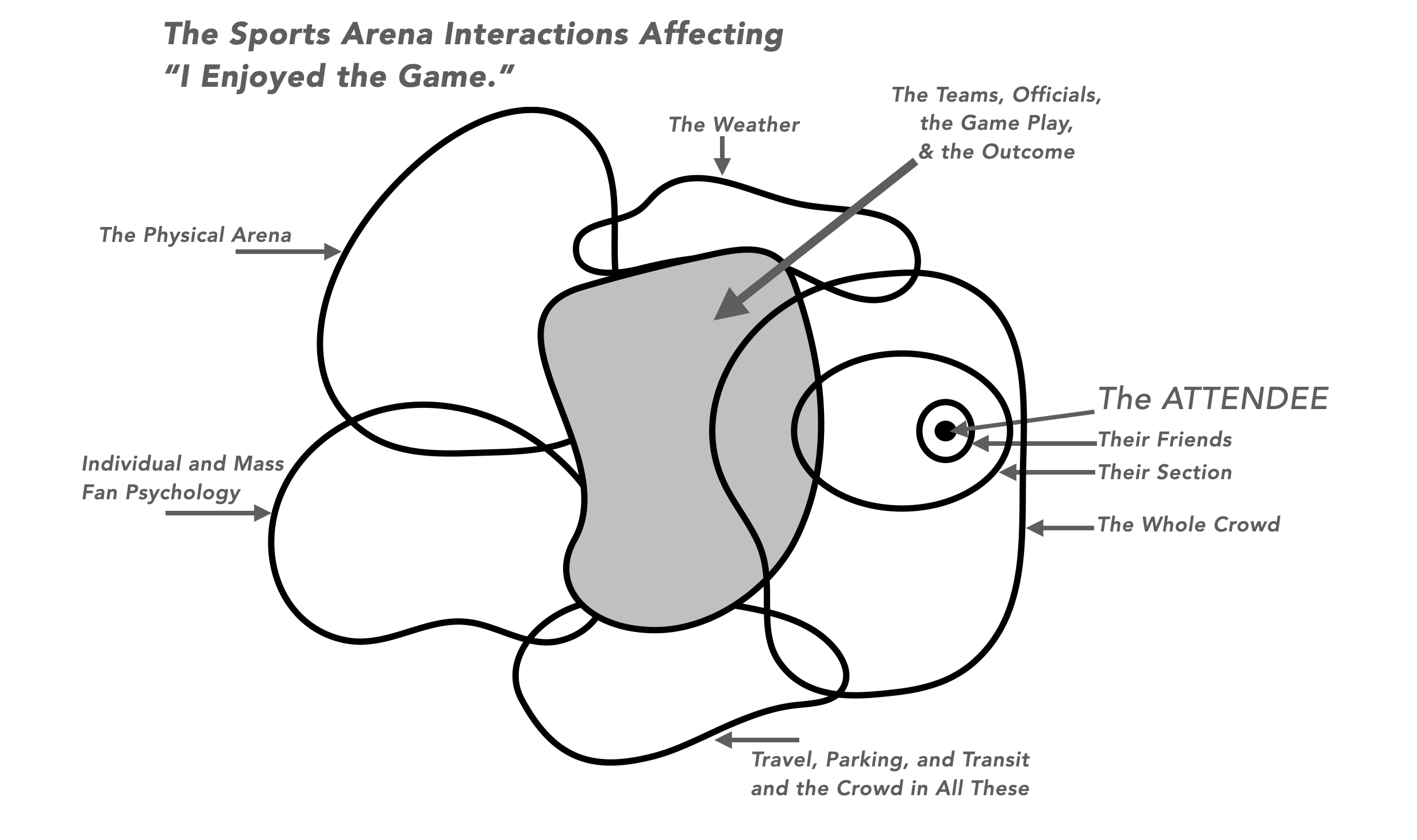

How, then, might we envision the influence of each factor within the complex situation from which emerges a decision to purchase? In my writing and teaching I rely on bubble charts to help envision complex parts. The example offered here considers influences affecting whether an emergent “I enjoyed the game” emerges for those attending a sports event. Each bubble summarizes rough groupings of “areas” or “parts.” I use bubbles quite intentionally for their irregular boundaries as no firm boundaries exist as a customer’s decision emerges — all boundaries are imposed by those of us studying these ideas. We must, then, allow ambiguity if we are to understand emergent results.

Considering Cause within Emergence

Once we see what emerges, how might we understand what caused it to emerge?

A start I find useful considers parts, events, and other causal issues on our bubble chart according to two types. Some parts,events, or interactions can be called extraordinary causes because they initiated what happened in this specific situation. Other parts are general causes in that they have causal influence but do not initiate what happens. While they do not initiate, these general causes are often responsible for both the magnitude and the direction of the complex or non-linear results. Without context, there are no outsized responses from exceptional causes.

This structure is explained in the writing of historian John Lewis Gaddis. It should be clear that every cause can contribute to the size of the outcome. While general causes don’t create the result, they amplify it. Thus, an exceptional cause might have little effect in one context and very large effect in a different context. With our focus here that means differentiation, for example, might matter tremedously in one situation and matter little in another.

Investigating causality in business using this approach helps us comprehend how factors interact leading to a result in our unique situation of category, product, industry, point in time, people, customers, market, and more.

Causal Discussion of Difference, and Distinctiveness

So many causal elements can influence an emergent decision to purchase that no complete list of factors can exist — the possible factors are uncountable. As noted above, many factors are cultural, emotional, rational, product related, information, lifestyle, needs, problems, or human desire. They also include causal factors specific to industry, product or service, category, consumer focus, and company abilities. Brand is always a causal factor as are the brand’s mental and physical availability. Both differentiation and distinctiveness can also be extraordinary causes of an emergent decision to purchase.

Imagine, then, a bubble chart of causes leading purchase to emerge. Assume, also, that both difference and distinction can be possible extraordinary causes. There will always be other extroardinary causes like location, price, recommendations and many general causes. The emergent behavior we want is that customers purchase a product which has a brand..

Traditional business science seeks Universal Answers such that following the dictates of these answers delivers predictable results and success. But there are no Universal Answers. What emerges will always depend on many of the specific and unique challenges of the situations.

That said, common patterns are usually found in what emerges across many situations. So, for example, there may be common patterns for consumable consumer puchases which are different from common patterns of consumers purchasing expensive durable goods and also much different from consumable purchases by businesses. The ways in which factors interact change depending on product type, market, customer value, customer knowledge, and much more. Let’s look at some examples.

Kobalt Tools

Kobalt Tools is the primary tool line for house-brand purchases at Lowe’s Home Improvement Stores. I spent 8 years developing advertising for this tool line — especially hand tools and power tools. Let’s just focus on hand tools.

Kobalt Tools is the primary tool line for house-brand purchases at Lowe’s Home Improvement Stores. I spent 8 years developing advertising for this tool line — especially hand tools and power tools. Let’s just focus on hand tools.

First, let’s talk about differentiation. Someone preaching differentiation as a “universal idea” would suggest that every tool in the line needs to be clearly different in a tangible way. That’s quite wrong. Consumers who come to trust the Kobalt brand want to be able to buy a deep 5/8” socket to fit their 3/8” ratchet drive. The Kobalt brand helps focus their shopping and what they need is a good socket. In fact, experience shows sales drop if the expected traditional sockets are made dramatically different according to universal ideas of differentiation.

But, for the Kobalt Tools line to sell well it needs some exceptionally different products. In his book Merchandise Forensics Kevin Hillstrom notes how critical it is that websites have some products which carry “magic.” For a product to be magic, it also must be perceived to be different. Most of my work with Kobalt focused on tools like these using advertising to show how and why their advantages were meaningful to customers. As with the car motor discussed in my last post, this factual and demonstration based advertising showcasing difference led to customers deciding “I’ve got to get one of those.”

From this work, we saw brand change emerge. Eventually, within research, people would tell us (unprompted) that the Kobalt brand was exciting and doing good things (as opposed to how the Craftsman Tool brand was perceived to be dying). Differentiation, then, can be an exceptional cause leading to the emergent result of “I want to buy that product” — whether it’s the different product or not. Yet, to have this effect it is not important that customers be able to articulate “product X is different in these ways ____” nor do they need to have dramatic desire to “get one of those” for every product in the line.

What about distinction? The Kobalt brand has been well managed by Lowe’s and has a distinctive blue, yellow, and black color scheme along with a clear and well maintained logo. The on-shelf packaging is also carefully managed. Net out, this distinctiveness plays a critical role in the store (and on the website) helping people find products. Perhaps more critically, if they are in Lowe’s searching for “a deep 5/8″ socket” then seeing Kobalt’s distinctive assets can lead to an emergent result of “oh, that’s right. Kobalt tools are good. I’ll get one of those.”

Thus, distinction is also an exceptional cause of emergent customer purchase decisions for Kobatl.

Decision to Buy a Specific Car

Bob Lutz has written some exceptional books based on his extensive executive experience at all three of the US automakers — Ford, Chrysler, and, most recently, General Motors. Along the path to an emergent decision to purchase a specific car, Lutz saw the need for customers to want the “whole car” — whether they were excited by it, felt they could depend on it, or any of many other possible emergent values. In fact, Lutz is quite critical of the ways GM brought in consumable goods brand teams who ended up dramatically hurting the whole cars as they followed their brand mythologies. (In my experience, most consumable goods experts lack the skills needed for hard goods just as I lack some of the key insights needed for consumable goods.)

Bob Lutz has written some exceptional books based on his extensive executive experience at all three of the US automakers — Ford, Chrysler, and, most recently, General Motors. Along the path to an emergent decision to purchase a specific car, Lutz saw the need for customers to want the “whole car” — whether they were excited by it, felt they could depend on it, or any of many other possible emergent values. In fact, Lutz is quite critical of the ways GM brought in consumable goods brand teams who ended up dramatically hurting the whole cars as they followed their brand mythologies. (In my experience, most consumable goods experts lack the skills needed for hard goods just as I lack some of the key insights needed for consumable goods.)

Notice, though, Lutz did not say the car had to be thought to be different by consumers but to be a product they “wanted.” Want is an emergent emotion critical to economic success. Yet it is often ignored by companies becaue it’s not hot-blooded. Yet despite authors claiming “brand love” is critical, wanting the car is what is needed to sell it. Of course, there are always wome cars which owners might love with big emotions — perhaps a Chevrolet Corvette or a 12-cylinder BMW 7-series. Most satisfied customers, though, just enjoy their cars, like their cars, find them reliable, and any of thousands of other ways to indicate pleasure with a product.

This does not make difference unimportant. Instead, to be effective, difference must serve the process of “I like that car” with specific differences forgotten before the purchase is even made.

Distinction also plays a role in car purchases as we rely on branding elements along our path to deciding what to buy. Its role is very different here from, say, helping customers find the chips they like in the supermarket.

Certain cars are also superb examples of very poor choices around distinctiveness. Lutz complains often of the Pontiac Aztek (shown above) suggesting it is a result of the consumable goods branders. His primary mentioned concern is that it was made without knowing there were people who would want it. I’ll note it as an example of heavy handed design to be visually distinct. It was a mistake because those leading the project failed to understand how that specific distinctiveness played into customer purchases.

Another exceptionally distinctive car is the Tesla Cyber Truck (aka a trash can on wheels). We do not know how the idea behind this truck came into existence but it is very distinct — not in a good way. It’s quite easy to make a product that is objectively distinct which people respond to with disgust. It’s far more difficult to achieve a balance of distinction which matters.

So while distinctiveness is an extraordinary cause in the purchase of a car we must be careful about what we believe “distinctiveness” means.

Deciding to Buy a Supercomputer

Distinctiveness and difference are not always separate but can interact as part of the complex environment from which a decision to purchase emerges. Let me offer a rather extreme example with an early supercomputer.

Distinctiveness and difference are not always separate but can interact as part of the complex environment from which a decision to purchase emerges. Let me offer a rather extreme example with an early supercomputer.

Seymour Cray had worked at Control Data but broke away in 1972 to introduce his own supercomputer — the Cray Supercomputer. Today, this computer carries mythological power among those who know its history. Given the technology at the time, Cray achieved an exceptional result from brilliance and technological balance. Along the way, Cray made a choice which echoed through the halls of scientific and engineering institutions and companies. In an era of massive mainframe boxes, the Cray Computer was made in a circular shape with a bench-like platform. (See photo.)

Was this a choice of distinctiveness or difference? I don’t think we can separate them. Outstanding design involves distinctive shapes which are functionally important. Within the state of technology the circular design reduced the time it took for an electon to move from one part of the Cray to another. And the bench provided access to the extensive power supplies required for this computer.

Forty years ago I was part of the West Coast team evaluating supercomputers for then-behemoth General Dynamics. Within our team the Cray’s shape affected our discussion by being both distinctive and different. In part, it’s distinctiveness reminded us of how far ahead of its boxy Control Data competitor Cray had lept. General Dynamics purchased a Cray in 1985 or 1986.

Concluding Thoughts

A few conclusive thoughts:

- The relative importance of distinctiveness depends on the specific and unique details of brand, products, situation, industry, customer, and much more.

- The relative importance of difference depends on the specific and unique details of brand, products, situation, industry, customer, and much more.

- Both distinctiveness and differentiation can be done well within the uniqueness of a situation or both can be done quite poorly.

- Sometimes, these two ideas end up quite intricately interwoven and inseparable.

The question, then, is not “which is most important.” The question which matters is “exactly how do we use each (and both together) in our unique and individual situation.”

By the way, I’d be remiss if I didn’t note a surprising result for many marketers: All that emphasis on USP we are given? USP only matters sometimes. In fact, the USP idea seems to have become particularly popular because only one statment could fit within 30-second TV ads of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. USP, it turns out, is also not universally important for marketing.

In the next, and final, post of this seriesIn the next, and final, post of this series we engage the full battle by looking at the Ehrenberg-Bass research into distinctiveness and differentiation. We will learn a great deal from the research. And we will also learn how some of the broad conclusions people draw from the research shouldn’t be trusted.

Until then, be well.

©2025 Doug Garnett — All Rights Reserved

Through my company, Protonik LLC, I consult with companies as they design and bring to market new and innovative products. I am writing a book exploring the value of complexity science for driving business success. Protonik also produces marketing materials including documentaries, websites, and blogs. As an adjunct instructor at Portland State University I teach marketing, consumer behavior, and advertising.

You can read more about these services and my unusual background (math, aerospace, supercomputers, consumer goods & national TV ads) at www.Protonik.net. Roughly once a month, Shahin Khan and I discuss current issues in marketing on our podcast The Marketing Podcast available on Google, Spotify, the OrionX website, and Apple Podcast.

Categories: Business and Strategy, Complexity in Business, Marketing Research