Complexity: Science, History, and what Business Needs from Research

In the past year I discovered the essays of Isaiah Berlin. Berlin was a historian of ideas and the Enlightenment as well as a philosopher. Born in Riga and educated in the UK, he spent his life teaching at Oxford and is widely recognized for his lectures and essays.

Berlin’s work is refreshing for its intellectual depth — an intellect influenced by British and Russian traditions. His work is a strong meal which I had missed during my decades in business when I had too little time to dig this deeply. Berlin is also quite interesting for his extensive writing about the philosophy behind terms like “liberty” and “freedom.” His work shows how these words have always carried unclear definition and unintended consequences.

Most of all, though, it is refreshing to read about difficult topics which resist oversimplification — quite a contrast to the superficiality of most writing around business. He owns a place on my shelf with a rare set of exceptional authors and poets.

“That’s nice, Doug, but can we get to the topic?”

Good point.

To engage complexity we must learn to approach knowledge in more robust ways than are today found in business. (Background on complexity can be found at this link.) Businesses seem to presume “if it’s important it can be expressed as science” and that if a situation is important then ironclad logic is required to find the way forward. Neither are true. Some things in business can be as predictable as is demanded of science. Yet, in a general sense, success in business cannot be predicted. That doesn’t mean we can’t inform our choices or improve the ways we make decisions. With this in mind I’ve been searching out ways to consider the learning and communication around business success — especially to discover that which is not revealed through scientific approaches.

That led me to Berlin’s essay on “The Concept of Scientific History.” In this essay, Berlin considers enlightenment belief that history can be a science thus making the future of mankind predictable.

Today, management science has taken up the mantle of this idea by teaching that success requires only the following of known, predictable laws and universal truths. Berlin, as a result, has a great deal to contribute with his clear perception of the ways humanity arrives at knowledge.

Note: In the following I have kept quotes from Berlin long to keep the subtlety with which he sees pursuit of knowledge. My apologies to those who find them too long.

About Science and the Needs of a Science

The general population of people who do business would have a difficult time defining boundaries which make a science. Usually I see writers define “science” to be the “scientific method” in some flavor. That’s not quite enough and Berlin goes further.

“…the central criterion of whether or not a study is a true science is its capacity to infer the unknown from the known.” (p39)

“One of the criteria of a natural science is rightly considered as being its capacity for prediction.” (p25)

“It is the business of a natural scientist to be a theorist; that is, to formulate doctrines — true rather than false, but, above all, doctrines; for natural science is nothing if it is not a systematic interlacing of theories and doctrines…” (p27)

My training in maths is training in theory and the process of inferring via theory the unknown as we rely on what is known. Thus, the applied mathematician’s discipline seeks to find repeatable and reliable methodologies which help us peer into the future to see what is unknown. When it works it quite a noble discipline. (FWIW, I have a BA from U. Colorado and an MA – Applied Math from UC-San Diego focus on finite element analysis.)

A Continuum of Fields — From Math to History

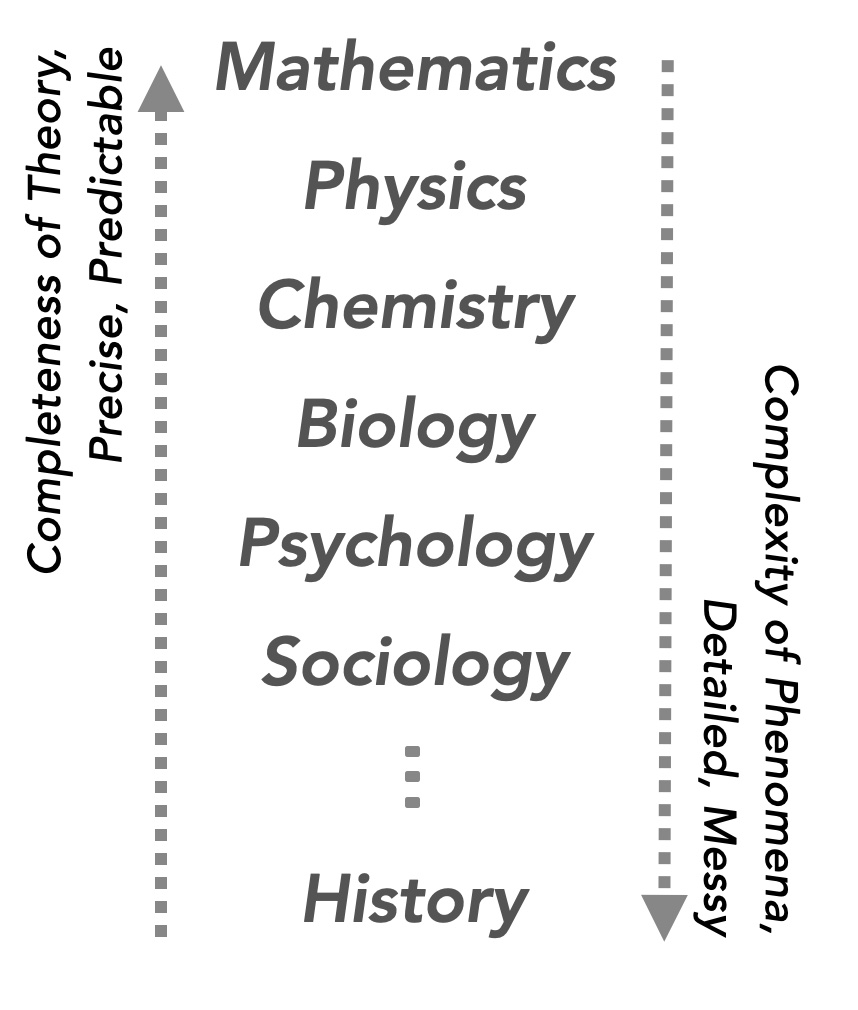

Berlin conjectures that there is a continuum of fields of learning (see illustration) from those which are most abstract to those which engage more fully with the real world. Assumed in this continuum is the idea that the more one is affected by the whole of the real world, the less complete, precise, and predictable a theory can be. At one extreme we find mathematics followed by physics.

is a continuum of fields of learning (see illustration) from those which are most abstract to those which engage more fully with the real world. Assumed in this continuum is the idea that the more one is affected by the whole of the real world, the less complete, precise, and predictable a theory can be. At one extreme we find mathematics followed by physics.

“The most rigorous and universal of all models is that of mathematics, because it operates at the level of the highest possible abstraction from natural characteristics. Physics, similarly, ignores deliberately all but the very narrow group of characteristics which material objects possess in common, and its power and scope (and its great triumphs) are directly attributable to its rejection of all but certain selected ubiquitous and recurrent similarities. As we go down the scale, sciences become richer in content and correspondingly less rigorous, less susceptible to quantitative techniques.”

Critically, we must abstract significantly from reality before we can rely on quantitative techniques. This abstraction doesn’t make the quantitative work inherently unreliable. But for areas concerned with a wider world it does make this work often unreliable and misleading. It also identifies a common error where, seeing the abstracted model as too simple, businesses just add more to the model — quickly leaving any realm of reliable prediction because they add more. When fields are less abstract, quantitative work must become understood merely to be a contributor while other ways to knowledge are in charge.

Where does the study of business fit on this continuum? Business lies quite close to history. There are important values we can obtain from scientific methods just as history is considerably helped by science. Yet understanding the whole of a situation is not possible through scientific approaches.

Economics as a Field of Study

A worthwhile aside is to consider economics. This quantitative challenge becomes particularly difficult for economics. Thus, Berlin observes:

“Economics is a science precisely to the degree to which it can successfully eliminate from consideration those aspects of human activity which are not concerned with production, consumption, exchange, distribution, and so on. If anyone then complains that economics, so conceived, leaves out too much… — among them questions which originally stimulated this science into existence — one is entitled to reply that the omitted sides of life can be accommodated … but only at the price of departing from the rigour and the symmetry — and predictive power — of the models with which economic science operates” (p36)

The more economists try to quantify the less they are able to comprehend of the world around us even though comprehending the world is the reason the field exists in the first place. Thus, a great deal of quantitative Econ today presumes equilibrium in markets. What has become clear over time is that this is a limiting and incorrect assumption. Economist Brian Arthur observes “By its very definition, equilibrium filters out exploration, creation, transitory phenomena: anything in the economy that takes adjustment — adaptation, innovation, structural change, history itself. These must be bypassed or dropped from the theory.”

Science Seeks that Which is Shared; History Enlightens Us with that Which is Different

Why do we assume that the things shared by “successful companies” reveal important truth? Unfortunately, there is a vast array of business writing which makes this assumption — such as Jim Collins’ Good to Great. Unfortunately, the studies usually only tell us a survivor bias answer — not insight. It turns out that what is different may be the most critical issue in business — not what is the same.

Berlin draws the comparison with history:

“…the business of a science is to concentrate on similarities, not differences, to be general, to omit whatever is not relevant to answering the severely delimited questions that it sets itself to ask; while those historians who are concerned with a field wider than the specialized activities of men are interested at least as much in the opposite: in that which differentiates one thing, person, situation, age, pattern of experience, individual, collective, from another.” (p39)

Assuming that the most truth comes from what is similar must be recognized for what it is — an assumption. Those of us in business need to become familiar with both nomothetic (abstract, law seeking, universal) and idiographic (unique, individual, specific) ways of seeking knowledge. Both approaches are necessary and every practitioner needs to discover ways to understand when each should be used.

Is History a Science?

No. History is not, and never can be, a science. Making history a science “remained a bogus prospectus, the child of an extravagant imagination, like designs for a perpetual motion machine.” (p25)

Berlin offers some interesting thoughts for those of us in business.

Considering attempts to create science by isolating specialized fields within history like history of technology… “These do indeed, at their best, satisfy some of the criteria of natural scientists, but only at the expense of leaving out the greater part of what is known of the lives of the human beings whose histories are in this way recorded.” (p33)

Theory also has only a narrow place in history. “Addiction to theory — being doctrinaire — is a term of abuse when applied to historians; it is not an insult when applied to science.” (p27)

This last piece is particularly critical. In our modern political environment, theory is considered more important than practicality and effectiveness. Communism in a theoretical approach. Much conservatism today is theoretical as are many parts of leftist or progressive agendas. Yet governing society, like business, is an inherently practical matter. Rather than celebrate the theorists it should be that we become clear about how they fail to govern effectively. Unfortunately, they are granted an appearance of success given that strict theoretical adherence today will win elections — despite leading to poor governing.

Many in business also have an addiction to theory. In part, it offers a way for CEOs and other executives to excuse failure when they “relied on the most universally recommended theory.” That said, there ARE theories which are a tremendous help as part of running a business. The trick for the executive is to understand which can be relied on and when they should be used.

Business, Historians, and Research

In business there IS some excellent, scientifically focused research which offers predictability for guiding decisions. Here I will point to the work of the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute around brand and marketing which is executed with great care. In general, though, the bookshelves of business bend near collapse under the vast amount of research claiming scientific basis but which is (a) not legitimately scientific and (b) entirely misleading.

Thinking over what Berlin wrote offers an intriguing idea — that business needs more research of the type produced by historians in order to learn about whole results and to probe the motivations behind action. Lest we make the mistake of assuming science is rigorous while history is not, historians work with great professionalism and care. Business would benefit from similar values. Consider.

“History is merely the mental projection into the past of this activity of selection and adjustment, the search for coherence and unity, together with the attempt to refine it with all the self-consciousness of which we are capable, by bringing to its aid everything that we conceive to be useful — all the sciences, all the knowledge and skills, and all the theories that we have acquired from whatever quarter. This, indeed, is why we speak of the importance of allowing for imponderables in forming historical judgement, or of the faculty of judgement that seems mysterious to those who start from the preconception that their induction, deduction, and sense perception are the only legitimate sources of, or at least certified methods justifying claims to, knowledge.”

“Capacity for understanding people’s characters, knowledge of ways in which they are likely to react to one aonother, ability to ‘enter into’ their motives, their principles, the movement of their thoughts and feelings (and this applies no less to the behavior of masses or to the growth of cultures) — these are the talents that are indispensable to historians, but not (or not to such a degree) to natural scientists.”

Lest we believe history is a fact free opinion fest “Without sufficient knowledge of facts a historical construction may be no more than a coherent fiction, a work of the romantic imagination, it goes without saying that if its claim to be true is sustained, it must be, as the generalizations which it incorporates must in their turn be, tethered to reality by verification of the facts, as in any natural science.”

“Nevertheless, even though in this ultimate sense what is meant by ‘real’ and ‘true’ is identical in science, in history and in ordinary life, yet the differences remain as great as the similarities.” (These quotes are from p49)

Notice that the tools used by the historian include “all the sciences, all the knowledge and skills, and all the theories we have acquired.” These are important tools. Rather than make these tools the most important truth, historians seek to comprehend a view of the “whole” — an integrated view — of what happened. In doing so, they make it make sense in the context of time and place and culture.

The similarities with what we need in business are important. We learn a great deal from honest, professionally prepared research into what company X did in situation Y — including enough of the situation to discover important learning. Unfortunately, any individual who writes these papers today will lack an absolute rule in their conclusion — yet those absolutes and universals are required for publishing, speaking opportunities, and promotion.

There ARE many errors which can be made in work like this just as there are many errors which can be made in work attempting to be scientific. A key one, which good historians manage adeptly as professionals, has to do with perspective:

“One of the difficulties that beset historians and do not plague natural scientists is that of reconstructing what occurred in the past in terms not merely of our own concepts and categories, but also of how such events must have looked to those who participate in or were affected by them — psychological facts that in their turn themselves influenced events. It is difficult enough to develop an adequate consciousness of what we are and what we are at, and how we have arrived where we have done, without also being called upon to make clear to ourselves what such consciousness and self consciousness must have been like for persons in situations different from our own; yet no less is expected of the true historian. Chemists and physicists are not obliged to investigate the states of mind of Lavoisier or Boyle, still less of the unenlightened mass of men.”

Over the past decade, we’ve become more aware of fallacies which can be made in work like this. We need not turn the world, though, into a “gotcha” fest where merely because the error could be made we assume that it has been made. In truth, all research is dangerous not only that which requires comprehending human motivation.

Don’t Case Studies Already Deliver this Work?

My own response is that they don’t. Case studies seem to have become miniature morality tales — told not to reveal insights into the specifics of the situation but to draw out of the situation something to prove a point.

That said, there may be groups of excellent case studies of which I am not aware. If so, I would love to learn about them — the discovery of new sources for business study is part of the process of pursuing this directions.

In this area, I have additional work to do to explore what’s possible to discover in the existing case studies.

Business Needs More of This Type of Research

I rarely read business books and consume, instead, copious amounts of general history and literature. Doing business is, after all, quite closely related to many of the acts and decisions and situations encountered in many areas other than business — government, the military, and more. I’ve often observed that anyone wanting to learn to solve problems in business should read Churchill’s six volume history of WWII. Yes, it’s written to celebrate his own achievement and, yet, there are tremendous passages which help us understand his considerable challenge. What challenge? A small island country attempting to thwart invasion by Hitler by creating a great alliance with the US and Russia. Reading like this brings considerable value to my work.

Yet I would prefer to discover business writing committed to this level of research and discovery. Some books about companies are thoroughly researched and strictly avoid drawing universal rules for business success. The Idea Factory about Bell Labs is one such book. This year I’ve readThe Cult of We and Flying Blind, The 737 MAX Tragedy and the Fall of Boeing which both offer similar value. And, a few of the autobiographies by executives are of similar quality — but not enough.

I am a bit disappointed, though, as books about companies today lack a specific depth which someone experienced in business might bring. Why? These books are primarily written by journalists — excellent journalists yet ones without experience running business. We are poorer that executives who write books mostly try to propound great theories which, in turn, build their ability to reap great speaking fees.

There are also some articles looking at the specific and the unique. I have been impressed with the articles and books of Henry Mintzberg. The strategic studies he published in the 1970s and 1980s seek to do exactly what I have outlined here — consider the truth of what happened in order to attempt to comprehend how and why the company progressed in the way they did. I have, fortunately, a great deal of Mintzberg left to read.

Once again, I offer these thoughts as part of discussion. There are no easy and absolute answers which magically make business an easy and predictable endeavor. So I look forward to other observations and hearing what others recommend for reading.

Be well.

Quotes are from The Proper Study of Mankind, An Anthology of Essays, by Isaiah Berlin, ed. Henry Hardy. Farrar, Straus, Giroux — New York, 1998.

Brian Arthur quote is from Worlds Hidden in Plain Sight, “A Different Way to Look at the Economy”, p193-199. Santa Fe Institute Press, David C. Krakauer, Editor, 2018

©2022 Doug Garnett — All Rights Reserved

Through my company, Protonik LLC, I consult with companies as they design and bring to market new and innovative products. I am currently writing a book exploring the value of complexity science for understanding business. Protonik also produces marketing materials including documentaries, websites, and blogs. As an adjunct instructor at Portland State University I teach marketing, consumer behavior, and advertising.

You can read more about these services and my unusual background (math, aerospace, supercomputers, consumer goods & national TV ads) at www.Protonik.net.

Categories: Business and Strategy, Complexity in Business, Marketing Research

Posted: May 12, 2022 01:20

DF Hobbs

Posted: February 6, 2024 14:35

Création de compte Binance