Pricing and Complexity (Part 2): Conjoint Analysis Can Undercut Price for Innovations

Marketing’s challenge is creating success amid the confusing complexity of customers who are human beings. It’s quite a fun, and often humbling, challenge for those of us who have dedicated our careers to the field.

Yet despite such clearly complex foundations, marketers, CEOs, (and economists) choose to believe that markets are well behaved. Assuming this makes the CMOs life easier — especially when communicating with fellow C-Suite executives.

The assumption isn’t always wrong — and there are periods of time or situations where the marketing problems a company faces are well behaved.

Unfortunately, there are also far too many critical times when the well behaved assumption is wrong. And that causes serious harm when working out price strategies with tools like conjoint analysis.

Price Complexity

Pricing has become a lost opportunity. Standard approaches end up leaving hundreds of millions of dollars of potential profit sitting on the table. Price failures may even lead to a company’s downfall when value doesn’t develop from its most critical and most innovative work.

Worse, today’s digital startups seem to know only about a price strategy of “be cheap”. Amazon appears to have never made money on e-retail sales and Uber, WeWork, DollarShave and Lyft are losing money at incredible rates. All of these profit failures are for the same reason: they deliver premium services but charge discount prices. (A package delivered next day to your front door is a premium service. When did we forget that?)

Too often it seems companies assume a price is just a number. Yet a price carries an incredible array of implications across markets and into every part of an organization. A price is a rich symbol worthy of a doctoral thesis using Jungian analysis or to be treated by semioticians like Umberto Eco.

Last month I took a first look at pricing’s complexity (using the term as complexity scientists use it). The post hit a cord and was followed by a fascinating and highly productive Twitter conversation which took place over the next 10 days.

That conversation eventually raised the idea of of Conjoint Analysis because it claims to be a smart way to make pricing fit the neatness corporations want. But while conjoint analysis appears to make pricing to fit neatly into companies too often it leads companies to fail to extract the value they should from the investments they make.

What is Conjoint Analysis?

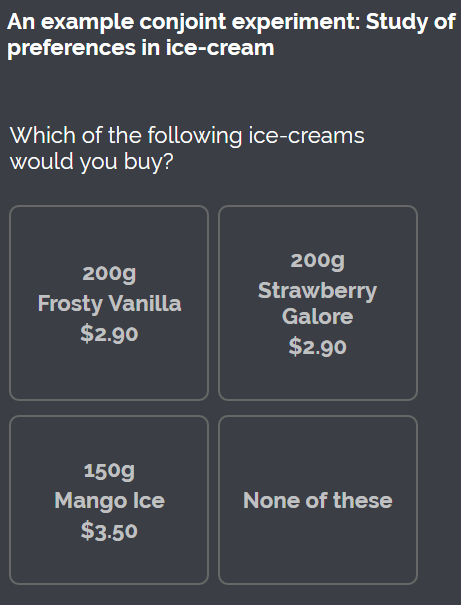

When marketers and product teams need to make decisions about products and about pricing, they often turn to conjoint analysis. Like any field, there are subtleties to conjoint analysis which take years to learn and require highly skilled practitioners. But it’s enough for this discussion if I lay out a simplistic view. According to Wikipedia:

‘Conjoint analysis‘ is a survey-based statistical technique used in market research that helps determine how people value different attributes (feature, function, benefits) that make up an individual product or service.

For conjoint analysis in marketing, a product or service is broken into attributes (commonly features) and a set of “options” are developed which are combinations of the features. Research is then conducted (qualitative for discovery, quantitative for reliability) where participants are asked to rank or rate the options. There are a number of ways to approach it. In some, price is included as an attribute and in others we learn perceptions by asking customers to predict the pricing for each option.

For conjoint analysis in marketing, a product or service is broken into attributes (commonly features) and a set of “options” are developed which are combinations of the features. Research is then conducted (qualitative for discovery, quantitative for reliability) where participants are asked to rank or rate the options. There are a number of ways to approach it. In some, price is included as an attribute and in others we learn perceptions by asking customers to predict the pricing for each option.

Complexity vs the “Well Behaved”

Conjoint analysis can only succeed within a narrow range of boundaries where customer response is well behaved. Otherwise, the ratings it returns are entirely unreliable and may be 100% wrong.

When market response is NOT well behaved, conjoint analysis can make things worse by leading companies to choose price strategies which lose considerable profit opportunity. Unfortunately, there are no absolute rules predicting when response will be well behaved.

Scientific complexity deals with similar issues as scientists have generally assumed problems are “well behaved.” Except perceptive scientists early in the 20th century started to notice key situations where things weren’t well behaved and predictable. Scientists started to explore those areas and complexity science was born.

Weather prediction is the poster child for ill behaved analyses because a tiny change in assumptions can produce wildly different results (the butterfly effect). Many surprisingly simple things also aren’t well behaved — faucet drips, turbulence in a stream, snowflake formation, bee populations, and much more.

An Example of Bad Behavior in Markets: New and Innovative Products/Services

The following example is artificial — but it reflects fundamentals from my 30 years of real world experience with new and innovative products and services. I focus here because markets are primarily NOT well behaved with these products — instability is a dominant factor.

The following example is artificial — but it reflects fundamentals from my 30 years of real world experience with new and innovative products and services. I focus here because markets are primarily NOT well behaved with these products — instability is a dominant factor.

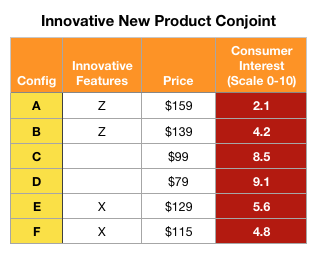

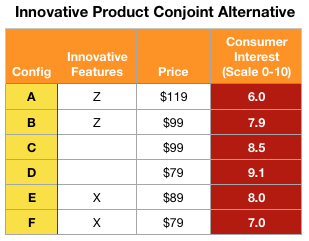

So let’s suppose we have a new product including the potential to build market strength with two particularly innovative features which are dramatic advances on past products. We have assembled the set of features and other attributes into 6 configurations. A conjoint analysis will create a table like this first one. Configurations A and B share an innovative feature called “Z” while configurations E and F share an innovative feature “X”. Configurations C and D are perfectly serviceable advances on existing products.

There are many ways to judge consumer interest but for simplicity I assumed we had a scale of zero to 10 and report the average interest as a number.

Some might call foul — perhaps the example mixes apples with oranges having different innovative features. I disagree. Whether we make the kinds of choices outlined here explicitly (as shown) or implicitly (usually without acceptance that we have made a critical decision), new product development constantly encounters this type of trade-off.

Looking at the table, many might think it gives us tremendous insight. It doesn’t. Worse, the table doesn’t tell us what it doesn’t tell us. And we’ll never know that something was missing because conjoint analysis gives the appearance of completeness — without being complete.

“The Problem Must Be that Prices are Too High”

Result like the above suggest that the innovations don’t have good “product/market fit” and would tend to lead companies to reject the innovations and focus on the incremental improvements. Fortunately, many executives know they need to keep pushing on innovations so they’ll conclude something a bit different — that the prices are too high.

Result like the above suggest that the innovations don’t have good “product/market fit” and would tend to lead companies to reject the innovations and focus on the incremental improvements. Fortunately, many executives know they need to keep pushing on innovations so they’ll conclude something a bit different — that the prices are too high.

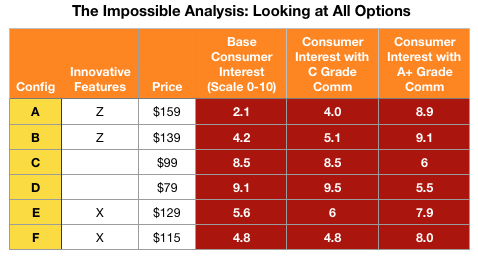

If a new conjoint analysis is funded using lower prices for the innovation (as in the second table), we’ll probably find the entirely expected result: Lowering the price for unexplained innovation increases interest in buying it.

But that isn’t the best answer for the company.

Finding a More Complete Picture of a Complex Situation

The market almost ALWAYS needs communication before it can accurately value an innovative new feature or product. This is made more important because most important innovations are hidden — not physically obvious — so they aren’t self-evident (see the Kobalt Double Drive for an example).

Notice that neither of the above conjoint analyses consider communication. My experience is that conjoint analyses assume communication is NOT a factor — this is a first way they assume the situation is “well behaved”.

This should scare us all. Omitting the impact of communication makes the analysis entirely inaccurate. What we need to know is what consumers would say in the market. And if there were to be communication, the conjoint needs to reflect what would happen if customers were informed about the product.

I’m not aware of any cost effective ways to create a conjoint analysis to do this. There would need to be two or three qualitative research projects in advance to learn where communication is critical and how to make it effective. Then we’d need to prepare at least three highly effective communications (A/B, C/D, E/F) in a medium which could be used in the conjoint analysis (often video). Then, there’s the cost of multiple conjoint studies to separate the possibilities. Total cost? Probably US$400K to US$600K.

So I’ve theorized what we might find with this impossible analysis and it’s a fascinating thing to consider.

So I’ve theorized what we might find with this impossible analysis and it’s a fascinating thing to consider.

In fact, it’s quite likely that the configuration rated lowest in the base conjoint study turns out to rate the highest if we could only look at the complete picture.

Where the prior analysis indicated a price under $100 was best, the fully thought through consideration shows that a price between $140 and $159 is probably best — a full $40 to $60 higher.

That higher price is not only important today. Prices likely erode over time so adding $40 to $60 adds to today’s margin will give you a far longer period time in which to reap profits from the innovations.

Let me also observe that in this case, doing only the conjoint analysis you can afford is worse than doing none at all because it leads to the worst way forward.

The Risk of Communication Mediocrity

Notice that I have added a theoretical conjoint analysis looking at what would happen if the communication fails in it’s job of generating as much interest in the innovation as it could. Why did I add this?

I’ve spent 30 years developing and delivering communication to drive interest, understanding, and purchase of innovative new products.. With very, very few exceptions, I’ve found advertising agencies and video producers are quite bad at new product communication (this is an area where agency mediocrity abounds).

So the hypothetical conjoint analysis needs to consider (for risk analysis) consumer response (a) without communication, (b) with mediocre communication, and (c) with excellent communication.

Not Hypothetical: The Drill Doctor Drill Bit Sharpener

Almost 20 years ago I was approached with the Drill Doctor — a product loved by many professionals but which wasn’t moving at retail.

Almost 20 years ago I was approached with the Drill Doctor — a product loved by many professionals but which wasn’t moving at retail.

Interestingly, a well known midwest US ad agency had done some research work and, following a 75 word product description, had asked respondents to rate their interest in buying the product. On a 5 point scale, the average interest was around a 2.5. In other words, they weren’t buying it. The ad agency recommended they not pursue a wider market.

I looked at the research. It clearly didn’t ask an informed consumer about their interest — these respondents knew nothing about the product. So my agency took on the challenge and we did research to learn how to communicate the benefits of the Drill Doctor.

Unsurprisingly, we found that people didn’t even know drill bits could be sharpened and certainly didn’t have any idea of the value they’d get from being able to sharpen them. Out of the research, we learned interest in the Drill Doctor flipped when we clearly showed 6 compelling values they’d get by being able to sharpen. These six values became the core of the communication strategy.

Over the next 8 years, our advertising was key to selling over 3 million units of a $100 product which sharpens $0.50 drill bits. Communication also drove exceptional sales of their $179 version of the product. Now, 20 years later, they retain strong big box distribution, the high end product still demands over $100 and the core product remains priced at $100. All for a product people said they didn’t want.

This example shows the high risk of conjoint giving a false negative. Certainly the agency had not done a conjoint analysis trade off of features. They had evaluated a single configuration and showed wrong conjoint is when communication is needed. Imagine that this problem lurking amid six conjoint configurations — you’d never know what you weren’t able to know. Worse, there would be zero probability of the conjoint analysis helping achieve the best profits.

Beyond Communication?

I’ve focused on communication because I have clear examples from my years working with new product introductions. Similar problems abound in conjoint analysis when the market response is ill-behaved for any reason — distribution channel, engineering challenges, manufacturing impacts, etc…

That said, I will take a moment to observe that ANY new introduction of a product with highly innovative features should START with specialized research learning how to create the most effective communication. That research will also reveal quite a bit about price elasticity because people pay the most for that which they value the most.

This research shouldn’t attempt to fit the square peg of “conjoint analysis” into a round hole. The company needs qualitative research — preferably an approach with focus groups like that which Carla Roberts and I have developed.

Note, also, that in our work we explore feature combinations to ensure the finished product has high interest from consumers. It executes a kind of exploratory conjoint learning without the errors discussed above.

Like Engineers, We Need to Watch for Complex Problems

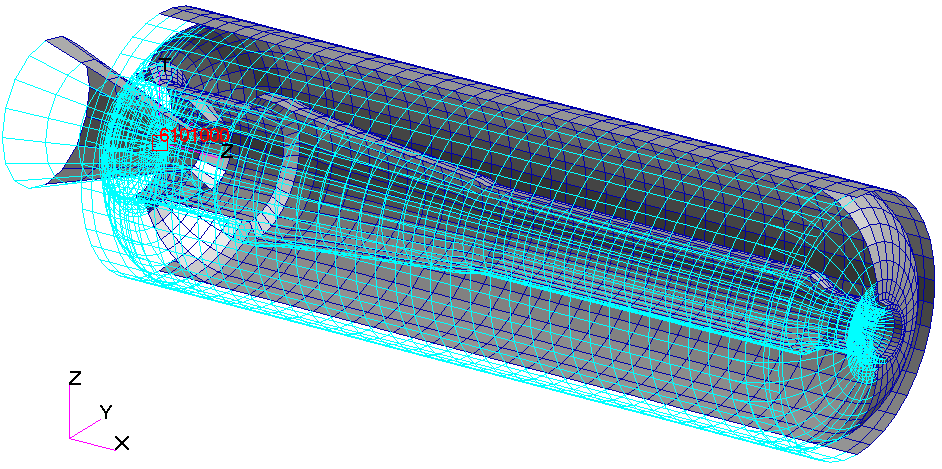

Straight out of college, I took my sparkling fresh math degree to San Diego where I worked at General Dynamics (Space Systems Division) supporting a sophisticated mathematical program for structural analysts (NASTRAN).

This program was based on an assumption that the structural response was “well behaved” — in this case could be evaluated with linear assumptions. It was the only practical way to analyze a large complex structure like an airplane body or a rocket (or their component parts). At core, well behaved structures have elastic deformation meaning the structure returns to original form when pressure is removed. This has been a highly effective assumption and we went to the moon relying on linearizing assumptions.

These assumptions are effective because engineers (like those behind the Apollo missions and those I worked with) are also always on the lookout for situations where the assumptions were invalid — where bad behavior begins.

And those cases come up. One engineer I worked with needed to look at what would happen were a mobile structure hit by a large blast. In that case soil compacts underneath (a plastic deformation — not elastic) then the structure rebounds and loses all contact with the soil — a hugely non-linear problem. I consulted on that project because the primary investigator knew how far out of the linear boundaries his analysis had moved.

Where and When is Market Response Ill-Behaved?

As with engineers, marketers need watch out for situations where market response is ill behaved. How do we describe that?

There is no universal approach. With conjoint analysis, though, we know market response is ill behaved when factors other than the attributes in the study have outsized influence on price. What might those be? Here’s a start:

- Effective communication is often critical to building price perception. This must be accepted.

- Customer price expectations are set according to sales channels. So market response should be assumed ill behaved when channel options are not yet defined or are in turmoil.

- Competitive response to the product can nullify or diminish innovation value. Such response invalidates conjoint analysis.

- Sometimes there are underlying and unexpected connections among features. In this case, configurations are not reliable groupings for looking at price.

- Worst of all, perhaps, the distribution channel’s perception of price is too often more important than consumer perception of price. When WalMart demands a low price most manufacturers jump and accept WalMart’s volume throwing smart pricing strategy out the window.

Accepting Complexity is Especially Critical in Pricing

Surveys among CEOs show dissatisfaction with the impact they are getting from innovation efforts. What I’ve described here is one very critical reason for that dissatisfaction. But this can change.

Marketers need to start learning ways to detect when a situation becomes complex — especially with price questions. Marketers can start by always assuming that market response to new, innovative product is particularly unstable and ill behaved — complexity is ALWAYS at work with innovations.

And here’s the beauty. Approach these kinds of pricing situations well and companies will generate far more profit from innovative developments than they have in past.

©2020 Doug Garnett — All Rights Reserved

Through my company Protonik LLC based in Portland Oregon, I advise a select group of clients to drive success with better marketing of new and innovative products. I also work with clients attempting to bring new life to Shelf Potatoes or take their existing products to new markets. You can read more about these services and my unusual background (math, aerospace, supercomputers, consumer goods & national TV ads) at www.Protonik.net.

Categories: Business and Strategy, Complexity in Business

Posted: February 10, 2020 19:42

Henry Coates