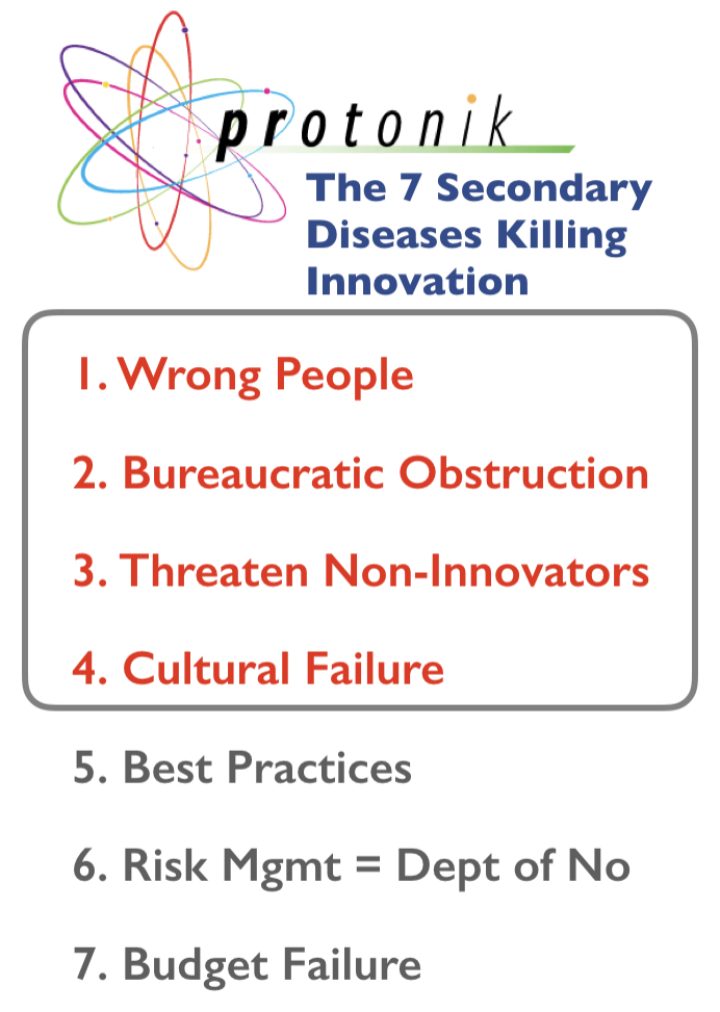

7 Secondary Diseases that Kill Innovation: Problems of People, Politics, and Culture

.

What kills innovation? What leads innovation efforts to fail to deliver the value they should? The ROI they should?

I’ve explored these questions in recent posts about the 4 Deadly Diseases that Kill Innovation (here and here). Sadly, these Four Horsemen of the Innovation Apocalypse are followed by a posse of Seven MuleRiders of Destruction.

The secondary diseases can be deadly as well. And with these 7, we move more deeply into exploring what’s behind the symptoms noted in the KPMG and Innovation Leader research reported in HBR by Scott Kirsner.

In this post let me deal with four of the secondary diseases — those that center around people.

Secondary Disease #1: Choosing the Wrong People for Innovation Projects

There is no way to over-estimate the importance of the specific people who manage and execute your innovation projects. Here’s a start on finding the right people.

Individuals are Key: Innovation requires individuality. Innovation is driven by specific people who see things differently and who have a commitment to see those things through to completion.

Unfortunately, we are in a period of peak bureaucracy — where companies want, somehow, to “scale” innovation and to do that through bureaucracies. It won’t work.

Any company which wants to execute brilliant innovation needs unusually perceptive leaders running organizations of unusually perceptive people — who together deliver genius.

Unfortunately, as Whyte noted in The Organization Man, bureaucracies try hard to kill genius. Genius requires an openness to serendipity. Genius requires people who make us uncomfortable. Genius requires giving people room to explore and discover – room for the accidental discovery that can deliver billions in profits.

Leaders are Key: Companies also make classic mistakes in choosing leaders to take responsibility for innovation. Two mistakes stand out in particular:

Many companies “buy” an outside innovation expert based on their claims to have the magic juice to create innovation nirvana.

There are times when this works. In my experience, those times are rare. When it doesn’t work, we often find guru like figures (lampooned in the HBO show “Silicon Valley”) arrive at the company and one or both of the following happens:

- It turns out they don’t have magic juice. They might have processes and theories but often they are best at selling themselves while being only mediocre at innovation. It’s appropriate to carefully review resume’ claims when hiring an outsider to lead innovation.

- They lack the ability or opportunity to build strength within the company culture. Great innovation can only take place when it fits the companies strengths. Too often these outsiders attempt to impose the innovation they want rather than find the innovation the company needs.

Other companies choose to promote from within. In general, I prefer this but it’s risky.

Too many companies use success with existing products as their criteria for selection. But we need to remember

“Managing a $50,000 product line in it’s first year is harder than managing a $500 million business in its twentieth year.” …Jack Welch in “Winning”

An entirely different approach to projects is needed to succeed when leading innovation. So choosing someone based on success in the tightly controlled world of existing products and services is usually an error.

A core problem throughout innovation is that corporations hire based on “skills” because skills fit well into boxes on HR forms and job applications.

A core problem throughout innovation is that corporations hire based on “skills” because skills fit well into boxes on HR forms and job applications.

But skills don’t tell you what kind of person you’re dealing with and whether they can be a productive part of teams who are innovative. The people you need have the right personality for innovation – usually a different personality than what is wanted elsewhere.

There are a lot of ways to sort people and their personalities. I have found it useful to consider a set of working/personality styles considered in the ISPI or the Innovation Strengths Preference Indicator ™. The ISPI ranks people on a range of factors in a continuum between “Pioneers” (who break new trails) and “Builders” (who come behind and settle the country).

The ISPI distinctions are critical – because both “Builders” and “Pioneers” may present very similar skill sets. So you can’t rely on skills alone AND you need all types of people in the company. In fact, builders are the core of any bureaucracy. Continuous improvement programs are designed around a builder approach. Every company needs builders to establish the reliable execution needed to grow the company once innovative products succeed.

Innovative products come about through Pioneers. That means companies must not pick builders to lead innovation. Yet, far too often, they do — because executives and peers may be drawn to people who fit neatly in the bureaucracy.

In an opposing error, there is another people failure: Sometimes companies pick people to lead innovation because they shock us. Too often, these are people who have developed the trappings of innovation without being able to deliver it. Someone who is shocking often talks repeatedly about Facebook’s “move fast and break things” motto but a breaker of things isn’t often a productive pioneer. True pioneers are often introverts who don’t particularly love rocking the boat – they just refuse to accept the compromises that bureaucratic peace requires.

Secondary Disease #2: Bureaucratic Obstruction

This is tricky territory. Bureaucracy is required for a company to succeed – no matter how big or small. But innovators, focused on their ultimate goal, are constantly frustrated with bureaucracy.

Managing the inevitable tension between innovation and bureaucracy is critical. Managed poorly it ends up as a mix of bureaucratic obstruction or outright war.

The KPI Deadly Disease is one place to look for how bureaucracy obstructs innovation. There’s also political risk when a builder supports innovation. In many departments doing the right thing to support innovation turns into political harm that leaders in the department can never overcome.

There’s another reality that leads to obstruction. Bureaucracies hate messiness. Yet some degree of chaos always follows along with innovation. This can be a daily irritation for people who put smooth running ahead of long term success. It can sometimes even appear to people in bureaucracies that innovations are designed to cause them to fail – so they want to keep as distant from them as possible.

What’s most frustrating to innovators is how a bureaucracy kills a good idea: by starving it of oxygen when it is ignored or loses its budget. Nothing more frustrating than to have discovered a powerful perceptive vision of the future for the company only to have it ignored by the people whose support you need to make it into a reality.

Executives must plan ahead and lead the organization to minimize the impact of obstruction.

Secondary Disease #3: Failure to prepare non-innovators to support innovation rollout

Innovators must take fighting this disease as their responsibility. While bureaucracy frustrates innovation, it is also incredibly important to company and innovation success. Innovation must eventually integrate into operations. This is true whether the company has separated innovation from, OR brought innovation into, core corporate operations.

Innovators commonly talk about how they wish co-workers would “wake up” and get a wider sense of company goals. Actually, that’s a polite way of putting it. I’ve heard a lot of harsh language used to describe those who are slow to embrace innovation.

We need to be more realistic. First, most corporations don’t incent employees to look at the big picture as KPIs are focused on narrow areas of action. While it’s frustrating when innovators encounter resistance, we must not expect fellow employees to risk a bonus that’s key to their child’s college fund.

And language matters. There’s an interesting article in Harvard Business Review suggesting that how innovators speak and how they express frustration may be a big part of the problem.

First, according to the article, innovation leaders tend to beat up the status quo. “Common wisdom in management science and practice has it that to build support for a change project, visionary leadership is needed to outline what is wrong with the current situation.”

Many innovators enjoy provoking the organization with ideas like disruption, “fail fast”, or listing everything wrong today. This creates fear among those not involved with (or with a tendency for) innovation and it doesn’t engage them in a positive way forward.

The study then found: “leadership was more effective in building support for change the more that leaders also communicated a vision of continuity, because a vision of continuity instilled a sense of continuity of organizational identity in employees. These effects were larger when employees experienced more uncertainty at work (as measured by employee self-ratings).“

Not much more need be said – this truth is quite obvious. Unfortunately, it’s quite challenging to sort through in practice.

Secondary Disease #4: Executive failure to engender cultural respect for innovation

Where to start. This topic includes so many things. But it starts at the top – with executives. And the first, biggest, and most destructive error from executives is putting up with, or even encouraging, political games that kill innovation. Executives must set the example and lead without being influenced by the pettiness of these politics.

Interestingly, in the KPMG/IM study respondents tended to blame peer managers rather than executives. But I’m skeptical. Politically savvy executives (are there any other types?) know how to have their people do the dirty work killing projects.

As a result, I don’t think the study is accurate. Again, it captures a symptom which is lower level management opposition. The disease is failure of executives to work in alignment.

While this could be a massive topic, there are three keys to responding to this cultural failure:

(a) Embracing innovation starts at the top. It can’t start anywhere else.

(b) The culture must allow – even embrace – the awkwardness and difficulties of innovation as well as the good and easy. If the culture has a fast trigger system of blame, innovation will fail. If the culture is made too uncomfortable by answers like “we don’t know yet”, innovation will fail. If the bureaucracy can’t handle a little messiness, innovation will fail.

(c) The corporate reward system (overt and covert) must be re-considered. Reward systems almost always fight against effective innovation. (See Deadly Disease number 4 for more.)

Executives must also create a culture with psychological safety. Research shows that psychological safety within corporations has become a serious issue today – perhaps made more serious by KPI abuse or “visionary leadership” threatening everyone with how bad the situation is. Regardless, many companies seem intentionally managed to make sure no employees enjoy life. It gets worse when KPI goals are assigned without the initiative and freedom to be able to meet them.

A sense of safety (psychological or job safety) is critical for innovation to succeed. Not only for the innovators but those in the bureaucracy.

A key part of psychological safety relates to the reward system. If an innovation was planned well, executed well, yet fails then there shouldn’t be punishment. It’s up to top executives to set the example to make this happen.

This CAN be done – I saw it in an incredible engineering operation I worked with which was doing difficult things on very tight schedules. The VP explained his rationale — one that created psychological safety:

“We all have a lot of balls in the air. So we are all going to drop one. When we do, our co-workers will tell us we dropped the ball. Then it’s our job to pick it up and keep going”.

It was incredibly effective for it’s honesty, acceptance that problems will happen, and no punishment as long as people did good work and were diligent.

The innovation may be technical, but the people may be most critical

As companies focus on tech based innovations, there’s a tendency to believe that creating innovative products based on technology is what’s most important. But the reasons innovative new things die is rarely failure in the technology. Instead, it can almost all be tracked back to the people in the company. And, following the lead of W. Edwards Deming, it’s the executives who must create the successful basis for innovative.

This post only skims the surface of how complex the people problems executives face may be. But, hopefully, it points the way to a far deeper respect for the complexities of balancing great innovators with the need for non-innovators to support new things. Hopefully it points the way to reducing the meddling of bureaucracy that kills innovation to creating psychological safety throughout the company so that innovation can succeed.

And what may be most exciting? What makes innovation work exciting for the entire company is finding ways past the frustrations which naturally must arise in these products — and doing that in ways that lead to success.

Next up: The Departments of “No!”. Click here for Part 4 in this series looking at diseases which kill innovation.

©2019 Doug Garnett – All Rights Reserved

Through my company Protonik, LLC based in Portland Oregon, I work with clients to drive innovation success with better marketing of new and innovative products and services — work which needs to start before market analysis. I also work with clients attempting to bring new life to Shelf Potatoes or take their existing products to new markets. You can read more about these services and my unusual background (math, aerospace, supercomputers, consumer goods & national TV ads) at www.Protonik.net.

Categories: Business and Strategy, Complexity in Business, consumer marketing, Innovation, Methodology

Posted: April 1, 2019 19:18

Strategic Failure and Management by KPI: Management Errors Which Kill Innovation (Four Deadly Diseases, Part 2) | Doug Garnett's Blog

Posted: June 4, 2020 04:54

Brain Science: How Process Often Shuts Down Innovative Thinking | Doug Garnett's Blog