Complexity vs Scientific Error: Masks in the Pandemic

In the US, our population seems to have arrived at two political extremes — those who reject science because they dislike what it discovers and those who counter with unqualified reverence for science. Both are wrong. Science is an effective tool and it is merely a tool — one we must consider objectively.

Unfortunately, a key weakness in science remains mostly unknown — a weakness which has done untold damage during the pandemic by leading to dismissal of the value of wearing masks in daily life.

Before we get to masks, let’s understand the weakness and how it relates to complexity science.

Complexity Emerges to Consider What Scientific Fields Miss

When humanity began, many millennia ago, to try to understand the world, all aspects of the world as it was understood were considered. In other words, we looked at the whole world and, despite the usual share of errors, we made a good start. Considering the whole world in every exploration, though, is too much of a burden to make progress. So we defined the field of science — at first focused primarily on the physical world — then developed sub fields like physics and chemistry hoping to discover ever more law-like universal ideas. These fields discovered many things. Yet any time we organize a field of study we must narrow our focus — declare some things valid and rule others out.

By the 20th century, even if we were to add together the scopes of all the fields of scientific study, we would no longer be considering the whole of the world. Worse, fields began to narrow further and faster when they were demanded to produce universal laws — forgetting that these laws can only be found with narrow questions. Thus, many fields generally practice where science is well behaved — NOT where they are messy through engagement with the real world. Narrowing did, in fact, make prediction more possible in science — except prediction also requires narrowness and ignores any broader portion of the world. For this reason, in my developing book on complexity science applied to business I suggest that rather than predict outcomes we should hope only to anticipate a range of possible outcomes. Unfortunately, modern humanity has come to demand more than this — that the world be predictable except it is not.

Truth will out. Scientists, especially those considering nature, climate, and the environment, discovered key times when traditional science failed them and they had to consider the whole. For example, around 1800 Alexander von Humboldt wrote about the whole of the environment on his journeys. Through the 20th century more and more situations were discovered where traditional science failed.

Scientific fields primarily assume that they can break problems into parts — reduce them — then add the parts together and, voila’, the whole is solved. Sometimes this works. Sometimes it doesn’t — as it didn’t for Humboldt. Complexity science focuses where the answers of the parts don’t describe the whole.

Complexity science explores situations where the whole result is more than, or different than, a sum of the parts.

Thus, complexity science is deeply involved with the environment where a “forest” is more than a set of trees. It is deeply involved with evolution where the future cannot be “pre-stated” (using a term from Stuart Kauffman). It is also deeply involved with the economy as the whole of the economy or a market is always more than or different than a sum of the parts.

What about Masks?

The value needed from a mask worn in the life of the general population is extremely different from the value needed from a mask worn in a healthcare facility. Specifically:

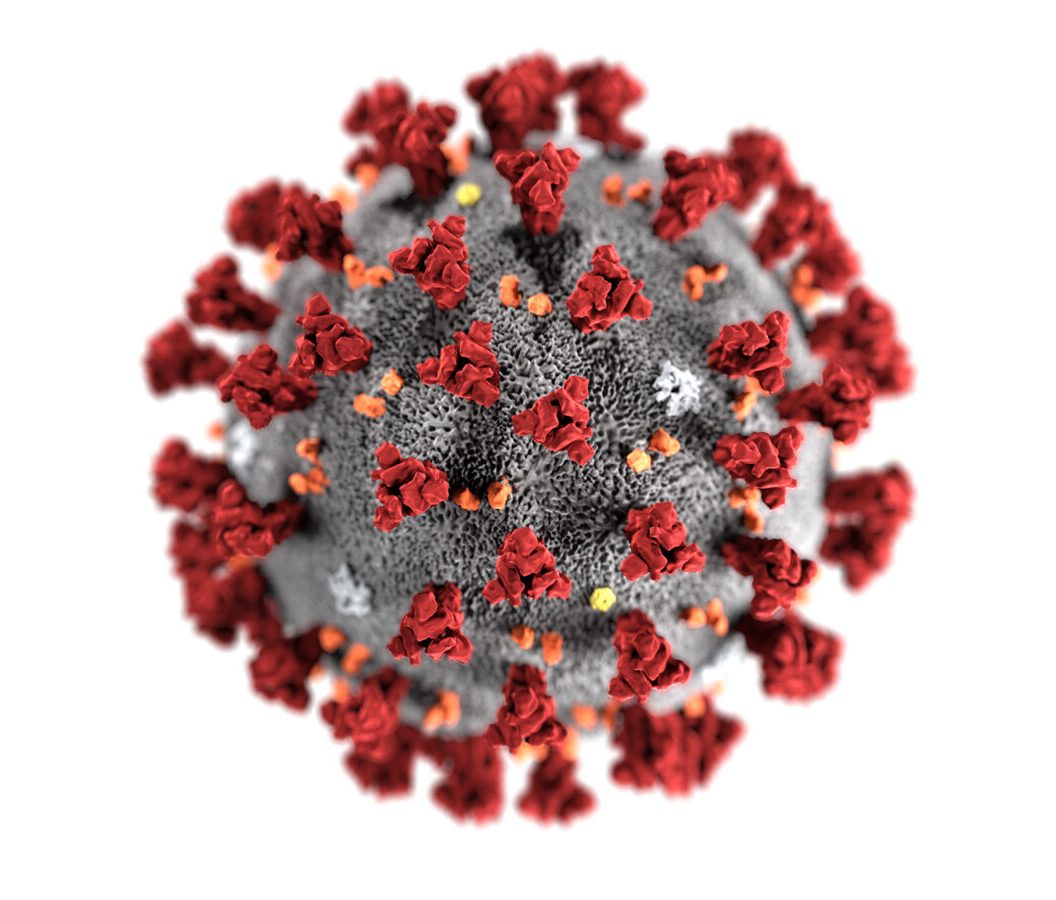

- Anyone working in a healthcare facility WILL encounter a critical load of Covid19 virus — enough to be infected. In this situation, then, masks need to build a Great Barrier preventing the viral invasion from making them sick.

- While healthcare work IS going to encounter a large viral load, in general life we need masks to prevent our ever being within a viral load even if we are accidentally near someone who is contagious.

These are very different challenges and I had expected different scientific exploration for each. My scan of scientific studies seems to indicate that hasn’t been the case.

Where Mask Science Focused

For past decades, mask science seems to have focused on the Great Barrier challenge. This makes sense given the constant need to protect health workers from the diseases regularly encountered in their high risk work. Except, when the pandemic hit it doesn’t appear they realized their focus needed to expand.

Mask science focused instead on particle size, sealing gaps in mask fit, and various ways of filtering particles then focused us on the N95 which removes at least 95% of all .3 micron particles and bigger. (There are many more types of masks for both industrial and healthcare use — but the N95 has been our primary pandemic focus.) These weren’t the right issues for the general population.

Mask science focused instead on particle size, sealing gaps in mask fit, and various ways of filtering particles then focused us on the N95 which removes at least 95% of all .3 micron particles and bigger. (There are many more types of masks for both industrial and healthcare use — but the N95 has been our primary pandemic focus.) These weren’t the right issues for the general population.

In a first mis-direction from this science, we were advised to wipe down our groceries early in the pandemic. This never made sense to me because it is a bacterial response — for removing bacteria. Even early evidence showed Covid to be airborne.

The second mis-direction, one which continues to do damage today, is that the primary mask advice from science has been on sizes of the virus, on filtration, and has always criticized cloth masks in statements which boil down to “but they’re not N95 rated.”

Considering our definitions above, the protection a mask offers to a hospital worker IS primarily a sum of the parts. The protection offered the general population is NOT. To consider mask wearing in the general population we need complexity science to consider the whole result.

The Whole: Masks in the General Population Doing Daily Business

As is common in complexity, considering this situation requires a combination of disciplines – fluid dynamics, airflow in enclosed spaces, human behavior analysis, and mask science. Sadly, not even the Santa Fe Institute has pursued this question from what I have read (including the SFI book on the pandemic).

With this in mind, I’m going to hazard a hypothetical discussion. I’m hoping that someone more deeply involved with the science can offer additional thoughts.

The Contagious Individual

Without a mask, someone who is contagious will spread viral danger long distances as breathing out is unimpeded. The longer they remain in the room, then, the farther their viral load danger spreads.

If the contagious individual is wearing a mask, though, their viral contagion will stay close to their body if they are standing still – perhaps within a 12″ cone around their head. In this situation, it seems the viral load will drop from the air before going any further. If they are moving about, there will be a spread of the viral load but neither as quickly nor as broadly as if they were unmasked. This means, if anyone in the room is contagious but wearing a mask, all others in that room are much safer.

The Person Who Needs Protection

Without a mask, inhaling brings incoming air from a large volume of air — a distance from the body. This could use some scientific work to get to specifics — but it is observably true. On the other hand, if they wear a mask, inhaled air comes from very near their head – perhaps a 6″ distance and a cone shaped volume from their mouth. Notice that this is true without requiring the mask to seal — as long as there’s not some major malfunction.

Their risk, then, of taking in viral load in each breath is far higher if they are not wearing a mask — because of air flow. This benefit seems to be entirely independent of mask type.

The Impact of Small Unmeasurable Actions

While we can study models of impact to reach conclusions, the gold standard in science would be some broad study of real life. Here we encounter another complexity identified challenge:

There are many things which are real in the world yet are too small to measure – ever. Yet the accumulation of these small impacts can drive major change.

Understanding the value of how these cotton masks work there is no way I believe we will ever have that conclusive real world test. There ARE things beyond our ability to measure for quantitative conclusion. And the broader the real world we need to consider (say, shopping in a grocery store) the less likely we can ever quantitatively measure the outcome.

Sometimes we must take actions without demanding pure logically conclusive rationales. Fortunately, with cotton masks the rationale seems so clear it would be silly to demand quantitative data before moving ahead.

The Whole Environment

I imagine our whole environment to be like the rooms of penguins I would see when my son played Club Penguin. People (contagious and not) randomly moving around. But the contagious no longer leaves a swath of virus in their wake and the not yet sick never encounter a viral load because inhaling takes air from so close to their head.

I imagine our whole environment to be like the rooms of penguins I would see when my son played Club Penguin. People (contagious and not) randomly moving around. But the contagious no longer leaves a swath of virus in their wake and the not yet sick never encounter a viral load because inhaling takes air from so close to their head.

In serious analysis, we would need to consider this statistically and derive probabilities of encountering viral loads. (We would also need to watch for unintended consequences.) Let me suggest we’d likely see something like a probability in most shopping, bus riding, and other active distanced activities to be zero or 0.5% if every one wears a mask and perhaps 50% if no one wears a mask and at least one contagious person is present. (Remember a probability of zero doesn’t mean impossible – just very unlikely.)

If we were in a classroom for a 2 hour class (as in one of my classes) the probabilities might be higher depending on distance from the contagious individual but probably no higher than a 10% or so while masked but 70% if unmasked.

Note that in both these situations I did not try to estimate the likelihood of someone contagious being near. Add that probability and the numbers decrease further.

What About the Advantages of N95 Masks?

The specific details of N95 masks generally don’t enter this analysis because mask type seems less important. That does not mean unimportant — but less important.

So while the N95 mask type is CRITICAL to hospital protection it appears the advantage of an N95 over a cloth mask is small — likely negligible — when we are living general life. It will have more benefit when situations might be more virus rich and where the wearer is more guaranteed to encounter the virus — for example if general population visits a hospital.

Discovering something to be important one place but not in another is common in complexity science — science searches for universal rules which don’t exist when context is dominant. Take a forest for example. Foresters spent decades believing competition between trees was the most critical management issue. Why? It seemed obvious and, perhaps, it could have been key in fields of corn. Except, it isn’t true for forests. Suzanne Simard’s work shows us that cooperation between trees, tree species, and the whole of other forest life (e.g. fungi beneath the ground) is most critical for regrowing healthy forests. Competition has a minor influence. (Her work is heavily informed by complexity as she focuses on the health of the whole forest.)

ALL Fields Suffer Similar Limitations

Whenever we define a field of investigation (then fund and organize that field) the resulting investigations no longer are effective when the whole is more than, or different than, a sum of the parts.

This has caused significant harm to business. Isaiah Berlin notes also that defining economics to be a quantitative science inherently forced economists to abandon the questions which were its reason to even exist. Why? Otherwise they couldn’t arrive at predictions.

Fortunately, complexity science has begun stepping in to comprehend how the whole comes together when it is different than a sum of the parts. And I am writing a book looking at how seeing the complexity in business changes our understanding of how success develops.

Conclusions and Requests

Let me leave with a few requests. First, we need mask science to change. At the same time, I am not scientist enough to elevate the discussion I’ve offered to “science.” Someone with better complexity science chops than I would deliver an important service with a thoroughly scientific investigation.

Further, humanity needs complexity science to remain focused on the whole and to refuse the compromises which would come with defining it as a “field” (in the traditional sense). We see already a tendency to limit it to the exploration of complex adaptive systems (CAS) — narrowness delivered behind an opaque screen of jargon. We need complexity science to continue to search the whole of problems — whether CAS or not.

Finally, humanity needs to come to see that the dangers in organizing fields affect all human endeavors. This narrowness rewards those who develop deep expertise without broad understanding — one of the most critical curses facing 21st century business.

For now, be well. And let’s stop discounting the value of cloth masks.

©2021 Doug Garnett — All Rights Reserved

Through my company, Protonik LLC, I consult with companies as they design and bring to market new and innovative products. I am currently writing a book exploring the value of complexity science for understanding business. Protonik also produces marketing materials including documentaries, websites, and blogs. As an adjunct instructor at Portland State University I teach marketing, consumer behavior, and advertising.

You can read more about these services and my unusual background (math, aerospace, supercomputers, consumer goods & national TV ads) at www.Protonik.net.

Categories: Business and Strategy, Complexity in Business

Posted: February 9, 2022 01:01

_

Posted: February 9, 2022 21:41

Doug Garnett