Pricing and Complexity (Part 1): Communication Affects the Pricing Wilderness

A recent Twitter thread pondered why so few companies dedicate much effort to determining the best price for their products. After all, “Price” is one of the 4Ps — apparently equal in importance to product, place and promotion. (You can view the thread starting here.)

Truth is that price IS an equal partner among the 4Ps. Yet marketers spend the most time on the three Ps which aren’t Price. Why?

My Experience with pricing.

I’ve spent over 30 years working with products, prices, marketing, advertising and sales. The bulk of my work has been with product introductions — bringing new and innovative products to market. As a result, I’ve worked at that key place where there’s huge flexibility in price — both a blessing and a curse.

Despite these 30 years working with products ranging from $10 to $10M I haven’t ever used the theoretical equations around price. Why not? They’ve never fit the innovative new product challenge.

My process has included extensive modeling in spreadsheets — primarily looking for those issues which are most critical for success. I’ve also spent considerable time working with consumer research which includes discussion of price.

What I’ve learned is that price, especially when pricing innovations newly hitting the market, is an incredibly volatile and unstable area. Equations presume a stability which simply doesn’t exist with new and innovative products.

Businesses are often surprised by this volatility — partly because it comes from the complexity which dominates price. Complexity is a surprise because price seems like it should be simple — coming up with some numbers. What businesses miss is that these numbers have to satisfy a hugely complex set of expectations while ALSO being an important symbol to both the distribution channel and to customers carrying a wide variety of meanings about the company and product. Oops. What happened to simplicity?

The following is the first post I’ll write about pricing — there will be more because I want to look at price complexity from a number of angles. This first post focuses on defining the fundamental issue of complexity in price using a key case study from my experience. With this idea of complexity established, future posts will explore more of the unexpected areas complexity arises with price.

Honoring the Complex

Over the past couple of years I’ve adopted language distinguishing between the complicated (those fundamentally linear things which can be individually isolated) and the complex (areas where interconnectedness, time dependence, and emergent factors make predictions exceptionally hard).

If you’re not familiar with complexity science and the idea of applying complexity science to business, let me refer you to my friend Rick Nason’s book “It’s not Complicated. The Art and Science of Complexity in Business”. Or, for a short summary, go to the blog of another friend, Andrew Everett, where he has published an excellent short summary of Rick’s book.

Businesses Embrace the Complicated, Ignore the Complex

Nason notes that in business, we tend to believe everything should be well behaved — that problems can always be “reduced” to smaller problems and once those are solved the overall is fixed. Further, executives tend to assume that a small error in our planning will cause only small difference in the outcome of an effort. And, so, most of what is taught in business schools fits with this complicated approach to problems.

Truth is that there ARE decisions and activities where complicated assumptions are entirely valid. In those cases, then complicated approaches are usually the best way to succeed.

But for very important and very critical business moves (like new product introductions), complicated assumptions are not only wrong, they lead to failure rather than success.

Pricing is at the Center of a Very Complex System

Complexity is often found to result from problems which reside within complex systems. The reduction approach noted above assumes that components can be solved separately then all brought together to solve the whole problem.

That’s not true with complex systems. In a complex system the parts are inter-related and a decision made in one area immediately affects the decisions for one or two (or all) of the other areas as well.

Complex systems are, further, time dependent so that the best decision seen today might end up having been the worst decision a month from now. As time proceeds, the world in which business lives changes.

Price lives in a complex system — one which is more dependent on the other components than on time. But sometimes time also has a dramatic affect on price.

After all, when the product changes (for better or worse), price strategy must adapt and when the price changes, the product must adapt. These cannot be separate. Price is tightly connected, in fact, to each of the other 3Ps as well as the rest of a company, to competitive moves, to distribution channel and to a wide range of customer behavior and psychology.

Pricing is not simple. Price is not complicated. Price is complex.

Pricing is Subject to Singularities and Discontinuities

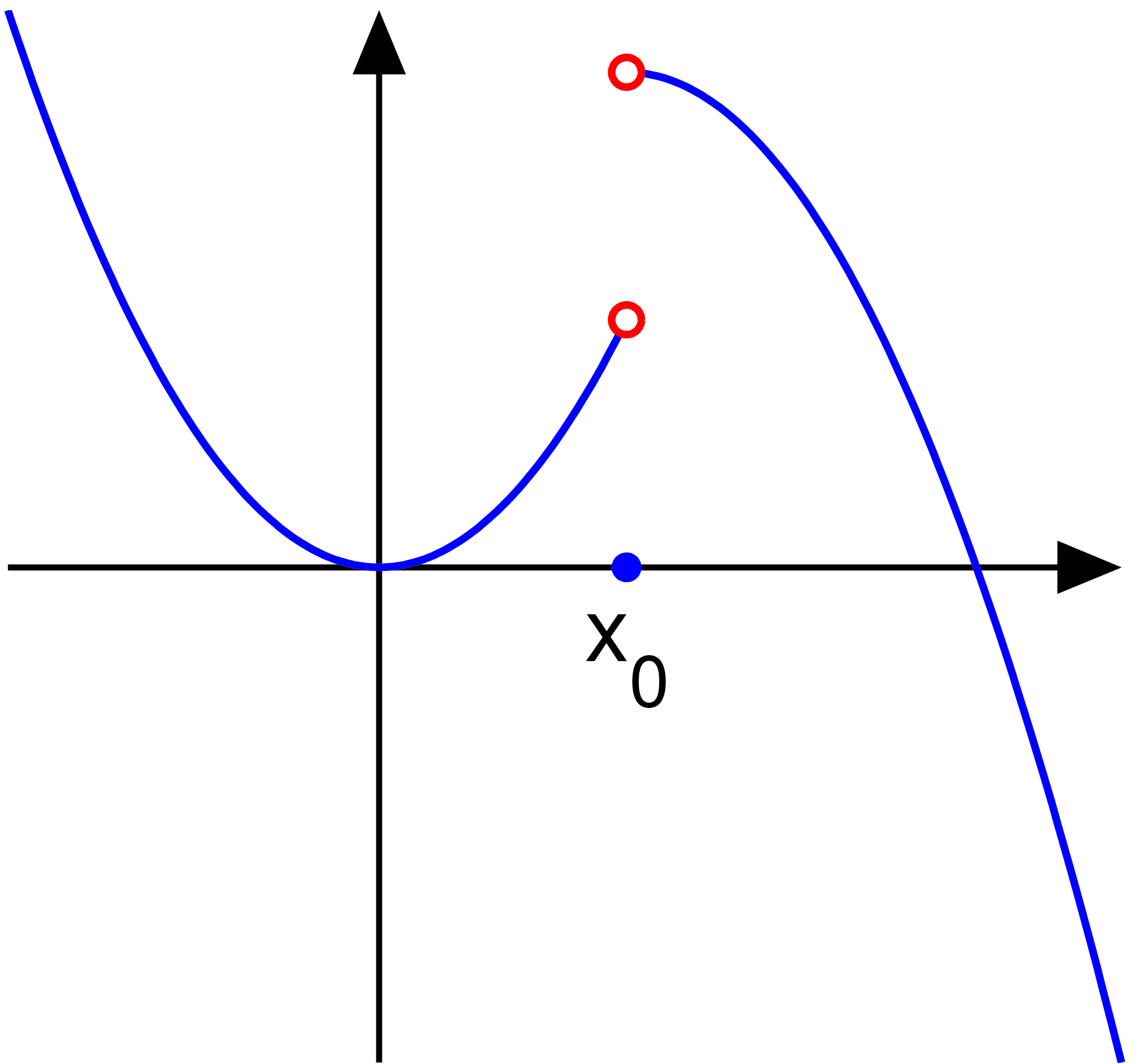

A Discontinuous Function

While I do NOT propose setting up equations for these ideas, let’s casually adopt a term from math — “discontinuities”.

In math, discontinuities happen when outcome jumps dramatically even when the input changes only slightly. These jumps can be quite disorienting to managers. Imagine a business which has been operating in the nicely behaved left hand arc of the graph shown here. At x=1.99998 the result might be 1.5 and at x=1.99999 it might be 1.51. Then, suddenly, given the discontinuity, the value at x=2.0 might jump way up to 5.0 or 6.0.

Business management lacks ways to consider anything which isn’t well behaved like at the first two X values. Further, as the company learns from the first two X values, there’s nothing to tell us our situation is discontinuous.

But why are discontinuities important? In business, discontinuous situations are where some of the biggest opportunities lie — right alongside our biggest challenges.

Price is one area where there are huge discontinuities based on connections to other parts of marketing.

Allegro Cookware, by Wearever

A Pricing Discontinuity Example: Allegro, by Wearever

Over 20 years ago I worked a project with the now defunct Wearever division of Newell/Rubbermaid. Wearever’s team had created a dramatically different set of cookware they called “Allegro”. It was visually different — square in shape — and delivered tremendous consumer advantages from the shape and from other features.

I was leading my agency’s drive to build communication for Allegro. At a key meeting I recommended, based on what we had learned in research, that they price the product between $300 and $400 for a 10 piece set.

The division president was shocked. He observed that Wearever had never sold cookware sets for more than $160 and he just couldn’t see it.

BUT… The product was excellent for the market — something confirmed in our research work. And we were going to support that product with the communication only possible through a 1/2 hour infomercial which would thoroughly build value to demand a higher price. My price recommendation was based on these facts AND an assumption that the communication would do it’s job (not all communication does).

This presented the executive team with a nasty discontinuity: $160 vs $360 based on the assumption that effective communication would make the difference. Few companies do well when faced with this kind of decision — and quite often the conservative decision ($160) wins over any other options.

Other companies go for no-man’s land and an average: “Let’s be safe and price it at $250”. This is the worst of all possible choices as it’s leaving vast money on the table assuming the communication works. But if the communication doesn’t work as hoped, then the product is priced far too high to ever sell.

Fortunately, my client — VP of Merchandising Dave Merten — understood the situation well. He agreed with the higher price recommendation and we proceeded with a $300 to $400 price point. Price testing showed, in fact, that $360 was the sweet spot where price, units, and profit performed best.

Corporate Price Analytics Can’t Handle 3X Variations Based Product or Communication Choices

What made this problem impossible to deal with in classic analytical approach is that without communication, price WOULD HAVE needed to be around $160. With communication, we supported a $360 price.

No analysis department I’ve ever dealt with in a corporation and few executive teams have a good handle on how to deal with discontinuities like this. Just consider the discontinuity graph above. The graph makes the situation far clearer than it ever is in the heat of battle. In business, we rarely know what kind of discontinuity there is — so we’re forced to work on instincts supported by experience and by research.

In my experience, companies walk away from billions in profits because their systems don’t have a way to manage a situation with drastic pricing discontinuities.

And these discontinuities don’t only come from communication. Single features (or feature sets) in a product, when well communicated, can double or triple price customers are willing to pay. Until the product is in-market at a price close to the “best” price for the product (best for profit, unit sales, revenue, future value, etc), you can’t do testing to prove the importance of the product features. But by then it’s too late — the product has been made.

“In the Absence of Relevance, Consumers Always Fall Back on Price” Sergio Zyman, The End of Advertising as We Know It

Zyman nails one of the most critical observations about the price crisis in companies today: there is little immediate penalty for a company setting price too low. In fact, the immediate effect of cutting prices generally makes everyone happy — unit sales rise, retailers love it, and the system is quite happy.

Except profits aren’t. Unfortunately that damage is very difficult to see and fits in that broad category of “lost opportunity” which is rarely (if ever) discussed.

The end result is that companies far more often err by pricing far too low than they err by pricing too high. The only times I’ve seen products overpriced come either when products are over-engineered for what consumers are willing to pay (I’ve seen this often) or when products mature and companies become hooked on their high margins — unable to anticipate their vulnerability and opening themselves to classic Christensen disruption.

What Should You Do?

In my experience, the first, and most important step, when dealing with a complex system is to accurately name it as such. And when you do that, also be sure to name those things which make it complex and how they frustrates decisions.

So spend some time thinking about your own price challenges and your unique complexities. Also think deeply about where/how complicated assumptions have lost your company profit.

Then watch for my next post — as we dig deeper into some of the surprising complexity which drives pricing errors — like the politics of your company.

©2020 Doug Garnett — All Rights Reserved

Through my company Protonik LLC based in Portland Oregon, I advise a select group of clients to drive success with better marketing of new and innovative products. I also work with clients attempting to bring new life to Shelf Potatoes or take their existing products to new markets. You can read more about these services and my unusual background (math, aerospace, supercomputers, consumer goods & national TV ads) at www.Protonik.net

Categories: Advertising, Business and Strategy, Complexity in Business

Posted: February 9, 2020 23:00

Pricing and Complexity (Part 2): Conjoint Analysis Can Undercut Price for Innovations | Doug Garnett's Blog